Since the Obama administration issued guidance in 2011 that directed schools to investigate sexual misconduct claims quickly and thoroughly, more than 300 accused students have filed lawsuits regarding Title IX proceedings.

Dozens have prevailed in their claims — often when the college had not been following Title IX guidance already in place, attorneys said — and many have reached settlements. Meanwhile, the Office for Civil Rights has launched hundreds of investigations into colleges' Title IX compliance.

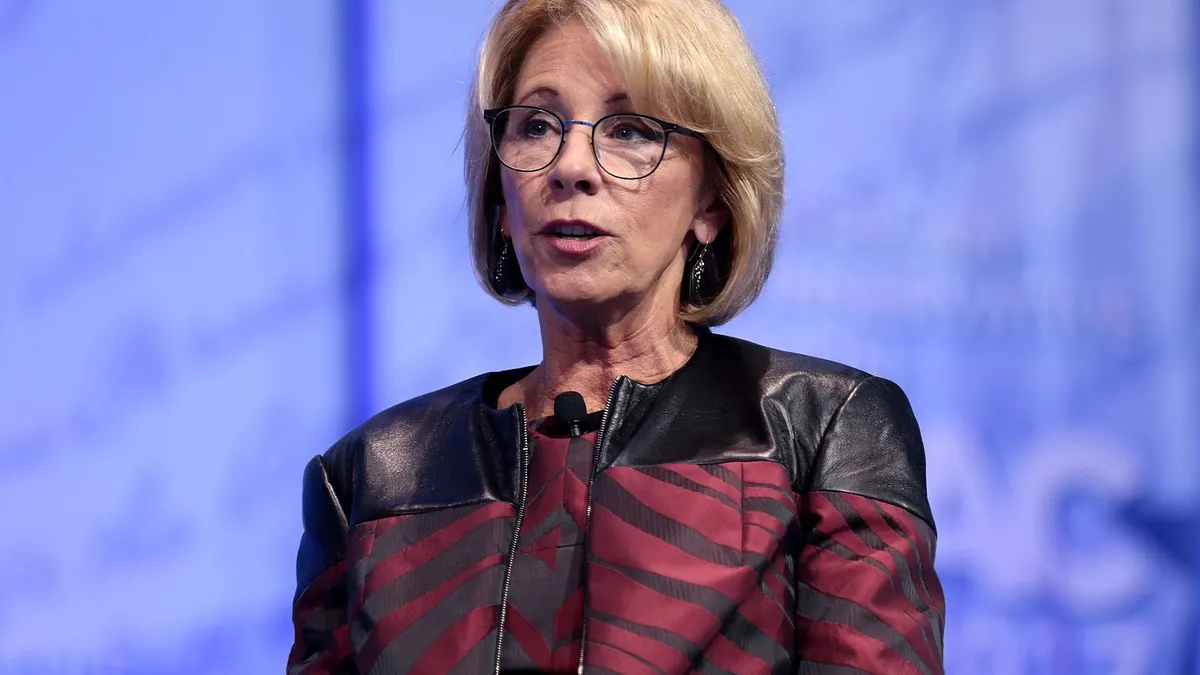

In an op-ed for The Washington Post, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos contended the now-rescinded guidance created an "opaque environment" that left colleges in the dark about what their legal obligations are. Under her leadership, the Ed Department is hoping to replace this guidance with formal regulations that would carry the force of law.

The department's proposed rule governing Title IX investigations, she wrote, aim to provide colleges with clarity and offer pathways for the accused as well as accusers.

Yet in conversations with Education Dive, Title IX and other legal experts expressed uncertainty and differing opinions for how colleges would be expected to carry out several areas of the regulations.

"This thing is a Rorschach test," said Peter Lake, the director of Stetson University's Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy. "People will see what they think they see in it, but when you really read the document it's either really inartful or it's unclear. That will be a problem because if we're going to have hard regulations, we're going to need to know when we're in violation of those. We can't be guessing is this one in or is this one out."

A spokesperson for the Ed Department said it does not comment on proposed regulations out for public comment, but wrote in an email that the "proposed rule seeks to ensure that all schools clearly understand their legal obligations under Title IX."

What cases will Title IX offices take up?

The proposed rule narrows the department's definition of sexual harassment to mean behavior that is "so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal access to the recipient's education program or activity." It also covers sexual assault or instances where an authority figure asks for sexual favors in return for perks such as a better grade.

These criteria would replace the Obama administration's less-stringent definition of sexual harassment as "unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature."

Some lawyers interviewed for this story said the change in language would require sexual harassment to effectively drive a victim off campus or subject them to escalating levels of abuse in order to require Title IX grievance procedures. In other words, colleges could be off the hook for disciplining some forms of harassment such as unwanted pressure for a date or the discussion of sexual topics so long as a student is still showing up to class, said Elizabeth Tang, a fellow at the National Women's Law Center.

This marks a sharp departure from guidance issued by Obama's Ed Department, which used a definition of sexual harassment that gave colleges the power to address burgeoning issues before they escalated.

However, others contend some of these concerns may be overblown. Samantha Harris, vice president for procedural advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), said that it's "an exaggeration to say that a student will have to be driven off campus before he or she can bring a complaint of harassment."

While isolated offensive remarks may no longer fall under the new definition, she said, colleges will need to review all claims of harassment in the context in which they occurred.

"It's a little bit hard to say, 'This would be harassment and this wouldn't,' because it's a very fact-specific investigation," Harris said. "Saying, 'I love you,' could be harassment if you're saying it a thousand times outside of someone's dorm window at night."

Harris expects the proposed rule will no longer cover cases in which "constitutionally protected speech," she said, is offensive to a listener but doesn't rise to the higher standard of harassment.

Regardless of whether a student files a formal complaint, she noted a college can implement supportive measures such as counseling, extensions of deadlines, work or class schedule modifications, campus escort services and heightened security in some areas.

"[I]f we're going to have hard regulations, we're going to need to know when we're in violation of those. We can't be guessing is this one in or is this one out."

Peter Lake

Director, Stetson University's Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy

It remains to be seen what level of harassment will trigger Title IX grievance procedures at different types of U.S. colleges if the proposed rule goes into effect. But whatever the outcome, lawsuits are a near certainty, Lake said.

"These regulations have ... the fate of being tested in the courts," he added. "It could be years before these things get finalized."

Amid a changing regulatory environment, some colleges have been looking to strengthen their codes of student conduct to bridge the gap between what the old guidance covered and what the proposed rule leaves out. Just as colleges can choose to impose punishments following a noise or drug complaint, they can write policies concerning behavioral expectations and sexual misconduct, said Cathy Cocks, president of the Association for Student Conduct Administration Board of Directors.

Colleges also must keep in mind their obligations under the Clery Act. The 1990 law requires higher education institutions that receive federal funds to disclose information to students about certain crimes, including sexual assault, stalking and dating violence. The Clery Act also requires institutions to keep a public log that tracks on-campus crimes as well as some crimes that happen off campus, depending on their circumstances.

How will off-campus conduct that impacts students on campus be handled?

In contrast to previous guidance, the new regulations would limit a college's Title IX responsibilities to cases of harassment that happen on campus or during a school-sanctioned program or activity.

Critics of the policy have noted that a high proportion of sexual assaults happen in the bars and apartments located just off campus. Further complicating matters are any incidents of harassment that happen online.

"An institution’s borders aren't so finite," Cocks said. "That's a piece of the regulations that need some clarification to really define what they mean."

The proposed rule makes no specific mention of what colleges should do in cases of virtual harassment, but it does state that colleges should consider whether the incident happened while a complainant was participating in a college's educational program or activity.

Colleges would still be free to cover off-campus matters through their codes of student conduct, the proposed rule states. What level of measures Title IX offices are obligated — or even allowed — to take for such incidents that end up impacting a student's life on campus is unclear.

"[It's] an exaggeration to say that a student will have to be driven off campus before he or she can bring a complaint of harassment."

Samantha Harris

Vice president for procedural advocacy, FIRE

Jennifer McCary, the Title IX coordinator for Bowling Green State University, is hoping for more clarity from the Ed Department in this section of the proposed rule, especially regarding situations in which a victim of a sexual assault or harassment that occurred off campus knows they still share the campus with the perpetrator.

"Are we able to go above and beyond what these regulations are stating and still address those things without concern that the institution will be responsible and liable for going against the Title IX stipulations?" McCary asked.

This is one area of the rule that may be ripe for change during the 60-day public comment period, which ends Jan. 28, said Daniel Prywes, an attorney at Morris, Manning & Martin. As of Dec. 12, the proposed rule garnered more than 40,000 comments, many of which echoed similar concerns about the off-campus provision.

Some off-campus conduct is "inevitably going to have some campus impact," Prywes said. "I'm not sure the department thought that one through completely," he added.

How would the religious expansion affect Title IX investigations?

Colleges are currently allowed to ask the Ed Department for faith-based exemptions from some Title IX provisions. But under the new regulation, schools would no longer have to first seek out the agency's permission to claim those exemptions.

Under pressure from LGBTQ activist groups and lawmakers, the Obama administration published a list of the colleges that had received exemptions. However, critics of the move said it was intended to publicly shame and accuse the institutions of discriminating against LGBTQ students.

That list is no longer publicly available, and if the rules go into effect, there wouldn't be a way to determine which institutions are opting out of Title IX and what their reasons were for doing so, BuzzFeed reported.

It remains to be seen how many colleges will forgo obtaining permission before claiming religious exemptions and what the effect will be on students. However, some critics of the rule fear it could open the door for higher education institutions to discriminate against LGBTQ students and other groups who come forward with sexual misconduct claims.

For example, if a college found premarital sex ran counter to its religious beliefs, the institution could choose not to investigate complaints of sexual assault from unmarried students, contended Tang, of the National Women's Law Center.

Only after the Office for Civil Rights launched an investigation into the college would that institution have to tell the Ed Department it is claiming a religious exemption and why.

"There's no rationale for that," Tang said. "The only reason we would have such a rule in place would be to protect schools from liability at the expense of student safety."

How would the proposed rule affect small colleges?

The new rule would eliminate the single-investigator model, in which a Title IX investigator typically interviews both the accused and the accuser and then either makes determinations or presents the findings. For some cash-strapped colleges, particularly small private institutions, this could be difficult to implement.

"Many schools simply don't have ... the staff for the model the department is proposing," Stetson's Lake said. "Many schools do not have the resources the [Ed Department] imagines they must have."

Bowling Green's McCary, who has served as a Title IX coordinator at small and large colleges, overhauled the Title IX office at the public Ohio university earlier this year. Doing so took several months of discussions and rewriting policies, conducting training and tweaking the process along the way to make sure the university is compliant.

"It's taken a lot of money and time and additional people, and this is something that's not necessarily a part of their job description," said McCary, who is also Bowling Green's assistant vice president for student affairs. However, she added, implementing those measures at a Title IX office could be an easier process at smaller institutions — if they have the financial means.

Those that lack the resources to implement the specific requirements of the regulation may end up pushing parties to agree to more informal resolutions that require less manpower than the live hearings called for in the proposed rule, The Atlantic reported. Those could include no-contact orders, counseling and training programs.

Others say pushing students toward informal processes — particularly mediation — could be harmful for victims.

"I have never recommended mediation for one of my clients in cases that involve intimate partner violence or sexual violence," said Katherine McGerald, executive director of the victim advocacy group SurvJustice. "The power structure is so unbalanced and people can be intimidated so easily. I mean, you're already afraid of this person. You're accusing this person of having hurt you, but yet they want you to sit together and hash it out?"