In 2015, Emory University's leadership had a moment of reckoning. A group representing black students on campus issued a series of demands that called on administrators to do more to address racism and inequality within the institution.

The private Atlanta university was far from alone. Around that time, students were issuing similar demands on campuses across the U.S. College leaders, however, often rejected them or were accused of glossing over their concerns.

Emory's response was different. The university moved quickly to organize a retreat on racial justice and formed a commission of students, faculty members and alumni to work through the concerns. It also set up a website to track its response to each demand, many of which, it says, have now been resolved.

That kind of quick action is key to controlling campus climate flashpoints, or issues that often arise with little warning and trigger "disturbances in the community or media" relating to issues such as diversity, free speech and gender, explains a new report from EAB that offers Emory's case as an example of how to effectively address a flashpoint.

Although colleges usually excel at monitoring traditional risks, such as natural disasters and financial hardship, they often fail to prepare for climate flashpoints, said Jane Alexander, senior consultant at EAB.

"Campus leadership should come together and proactively identify what those potential reputational risks are for their institution," she said. "Then, when crisis hits campus, this isn't something an institution hasn't thought about before."

We spoke with Alexander to learn more about where colleges go wrong when addressing campus flashpoints and what actions they should take instead.

Editor's note: This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

EDUCATION DIVE: All eyes are on higher education right now, and college can be a favorite punching bag for political pundits. How does this spotlight change how university leaders need to respond to climate flashpoints?

JANE ALEXANDER: University leaders can often be caught flat-footed in the moment. Traditionally, they have had two, three, four days to come together to decide on an appropriate response and put out an official statement. But in the world of social media, that kind of wait time amplifies the conversation.

If university leaders aren't responding, somebody is going to fill that vacuum and respond for them, and it's usually the campus community, with students and alumni jumping in the first day or two after an instance happens. They're spinning the story; they're controlling the message.

University leaders need to respond much more quickly, even if it's issuing a holding statement that says, "We'll get out something in 24 hours with more information, more detail." They can no longer take this consensus-driven, slow, "We do it all in committee," approach.

If you're abandoning a consensus-driven approach, how do you make sure somebody isn't making mistakes?

ALEXANDER: We recommend universities assemble an agile response team. We think of this as a dedicated flashpoint strike force, so this is not a standing committee. Members of the team are designated ahead of time. They're core campus leaders, maybe from student affairs, public safety, the president's office.

You determine ahead of time what the plan is for when a crisis unfolds, and then most importantly, who has that final sign-off authority and who speaks for the university. When a flashpoint strikes, there's no confusion about, "Is the coach supposed to speak for us, or are we supposed to speak for us?" People know what their goals and responsibilities are.

Higher education is not unique in experiencing climate flashpoints, but it may be held to a higher standard in its response. Why is that?

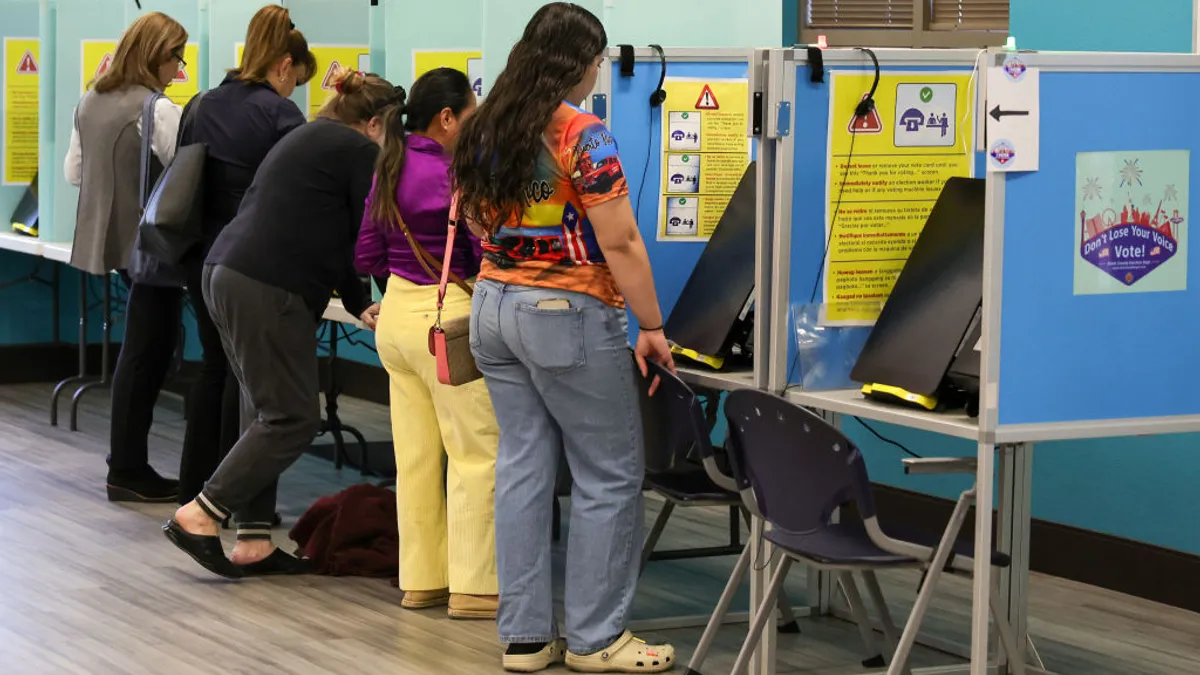

ALEXANDER: Students coming onto campus are very socially aware. They have developed strong identities. They are increasingly more diverse, and they are expecting universities to uphold values that are consistent with their own.

Millennial and Gen Z students have these same expectations for businesses. Anything they consume or buy, they want to see those companies representing values that they hold. They're expecting the university to go above and beyond traditional boundaries to address concerns and society at large.

Say a college doesn't have a good structure in place for addressing flashpoints, or college leaders err in their responses. What does the road to recovery look like?

ALEXANDER: In those instances — and I've seen so many happen — it's very important to get those core leaders in a room, come up with a plan together and put out a very strong statement, which should probably be at the president's level.

After what may have felt like a cover-up or just a debacle in communication, getting your statement clear, making it values-based and providing regular updates with as much information as you are allowed to share is really important.

How often should college leaders be discussing potential campus flashpoints?

ALEXANDER: The institutions that have this front-and-center are having discussions at the cabinet-level about every six weeks. At one university the president asks the communications team to keep a running list of all the potential flashpoints that could happen at the institution; they look nationally and locally. That's good practice.

What online tools are available to help institutions in their responses?

ALEXANDER: Social listening is a practice businesses have used for the past five or 10 years, but higher education is only just now catching onto it. The more sophisticated communication shops on campus will have software that will listen across the entire internet.

You can filter it and pull out trends to determine if conversations are happening nationally or locally. Who's influencing those conversations? Are we talking about the alumni donors? Is this current students, prospective students? That allows the institution to highly target its response. They can also see a flashpoint gaining legs, so they know they need to be ahead of it and prepare for impact.

Many universities will respond to flashpoints by launching a task force and issuing a report with recommendations. What can they do to get beyond that?

ALEXANDER: That can often feel like a very traditional approach to nuanced and highly charged, fast-moving issues that students are very, very passionate about.

We recommend what Emory University has done. The students worked closely with administrators to do this, but it was student-owned. It was a wonderful moment where there was a responsibility on the part of the students to address the concerns and to work with administrators to make the institution a better, safer place.