Colleges' relationships with online program managers (OPMs) are in the spotlight. As institutions expand online to lock down new revenue streams, stakeholders are questioning how those outside partners are affecting program cost, student data and institutional autonomy.

Supporters, meanwhile, have long argued that such deals provide colleges with quicker and deeper access to capital and could help them cut costs by streamlining internal functions.

But there's a bigger debate underway, and it focuses on the nature of these deals: Should a college hand over total control of its online programming to a third party, or work with them piecemeal as it builds its own OPM capabilities? The range of potential partners is also vast, covering all-inclusive providers like 2U, as well as smaller firms with specializations, such as instructional design.

A new report from the education market research firm HolonIQ seeks to better understand that landscape, and in doing so, widens the definition of OPM.

"It's going to be a whole bunch of different models and options," said Patrick Brothers, managing director and co-founder of HolonIQ. "Innovations like that are messy at the start."

To call out current patterns, the report describes the sector using the broader term "OPX" — with X to signify whatever job that company is doing — and breaks down the OPM market into four groups:

- Generalists (for example, 2U, Noodle Partners and Wiley Education Services)

- Specialists (StraighterLine, Orbis Education and InStride)

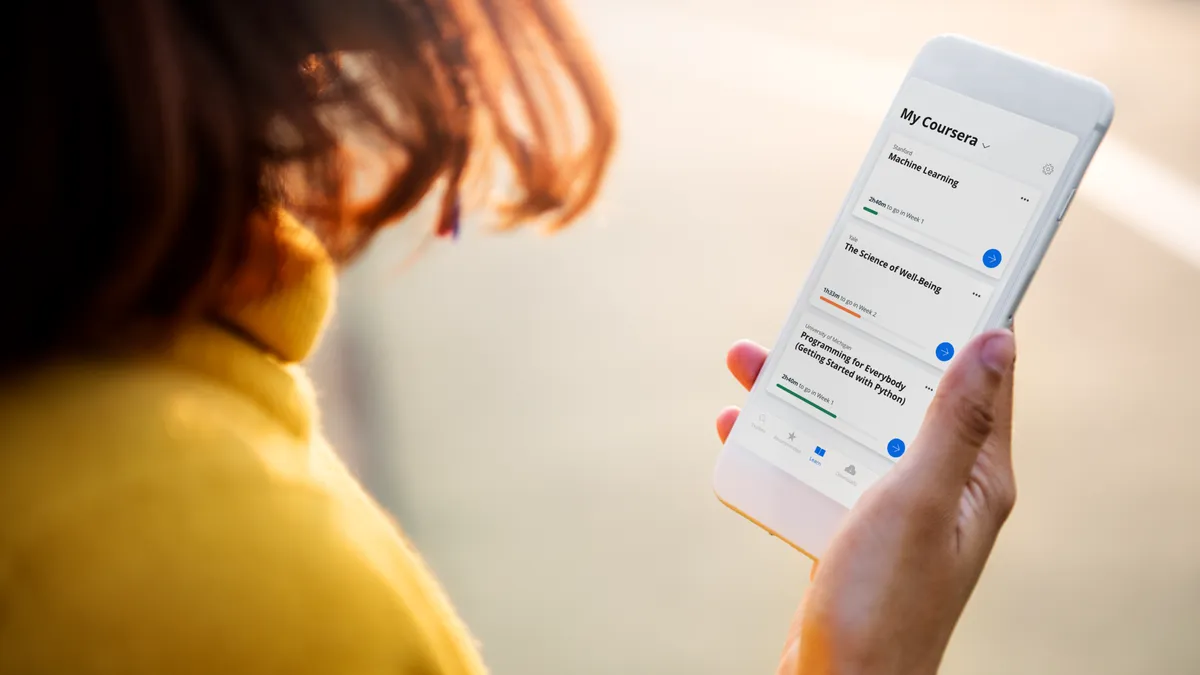

- MOOCs (EdX and Coursera)

- Universities (Grand Canyon Education, Arizona State University's Cintana Education and College Consortium)

Education Dive talked with Brothers about how he views the global OPM market, which his firm expects will reach $7.8 billion by 2025, and whether more unbundling is on the horizon.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

EDUCATION DIVE: In your report, you use "OPX" as an umbrella term that includes, but is not limited to, "OPM." What is X?

BROTHERS: OPM doesn't capture the breadth of services plays that are happening. New players are coming in and saying, "We're not managers, we're enablers," and linking that to revenue-share versus fee-for-service and more hybrid models; positioning themselves as underlying platforms versus on-top managers. There are also other models such as MOOCs-as-an-OPM or groups from specific capability blocks becoming OPMs.

Rather than replace or displace OPM, we're saying it's really OPX and X could represent either "insert model here," or it could be a bit like CXO — it's a C-suite role with different functional expertise. Even the really big OPMs, like 2U and Pearson, are changing their strategic positioning and saying, "You as the university, you are the manager, you are the owner, you are the credential."

The report shows the industry is evenly split on whether universities worldwide will take a bundled or unbundled approach to outsourcing through OPMs. Do you have any thoughts on which would be more likely, and why?

BROTHERS: Looking at it from an organizational-capability perspective, there's a real attraction to partnering with someone who has the scale to lower the cost of acquisition. Coursera, for example, is saying for its degree programs that it can tap into a large global cohort and have the systems and scale to help a partner achieve student acquisition at a much lower cost. In an extreme edge case of unbundling, it's much harder because each support element is smaller as well.

In general, we're seeing that people like the idea of unbundling and being able to pick and choose. But it's just more practical right now — and it's more appealing as well because it's so competitive between universities — to partner with someone who has scale and experience. They might still offer the same spread of unbundled services but can bring it together in one offering.

Will the industry move to an unbundled approach over time?

BROTHERS: Most people think the long-run trend will be toward unbundling, but it's not something that happens in five or 10 years.

That's tied to universities being able to develop their own capabilities.

BROTHERS: One of the trends is the concept that every university is replicating some of the same content — say, general education — which raises the question of whether it makes sense to have a highly unbundled, fragmented space when instead they could pull together and leverage similar resources to achieve some of the more generalist parts of higher ed and then unbundle for the specialist, higher-end parts.

We've seen that, and you call it out in your report, with groups like Outlier.org and College Consortium. Will we see more attempts to share or otherwise scale curriculum?

BROTHERS: Outlier.org is a really interesting breadcrumb for that. StraighterLine has been at it for a while and College Consortium is really interesting, too. It's one of those things that should be so much bigger than it is, but it's still not a trend.

Why not?

BROTHERS: Competition. Inherently universities mostly see each other as competitors, and the digital space only serves to amplify that. You'd have to ask yourself, if you were a general, nonspecialist, small-scale university, what is going to make you stand out in a digital space that's crowded and expensive to acquire students?

We've seen a few perspectives around this conversation. Institutions with large introductory classes use that scale to support smaller, higher-level courses, whereas smaller colleges are more likely to see the benefits of sharing because they don't have those economies of scale. Did any pattern emerge in your research?

BROTHERS: It follows the theory we're talking about. Things like College Consortium should be enormous, but there are some idiosyncrasies within U.S. higher ed. It feels like a real loss for the industry, but the sharing mechanisms are just not right yet.