Back in March, people began trickling into Calvin University's health center complaining of symptoms such as body aches and sore throats. The students and employees tested negative for the flu, leading campus officials to suspect they'd come down with COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

At the time, coronavirus tests were in short supply, leaving President Michael Le Roy disconcerted and frustrated. "It was a very, very sobering experience," he said.

Deciding that access to reliable viral tests was integral to the school's reopening plan and that he couldn't wait for a solution from the government, Le Roy got to brainstorming how he could acquire kits for everyone slated to arrive on the Grand Rapids, Michigan, campus this fall. He consulted with Calvin's biology and chemistry faculty, who suggested the school tap into the private sector.

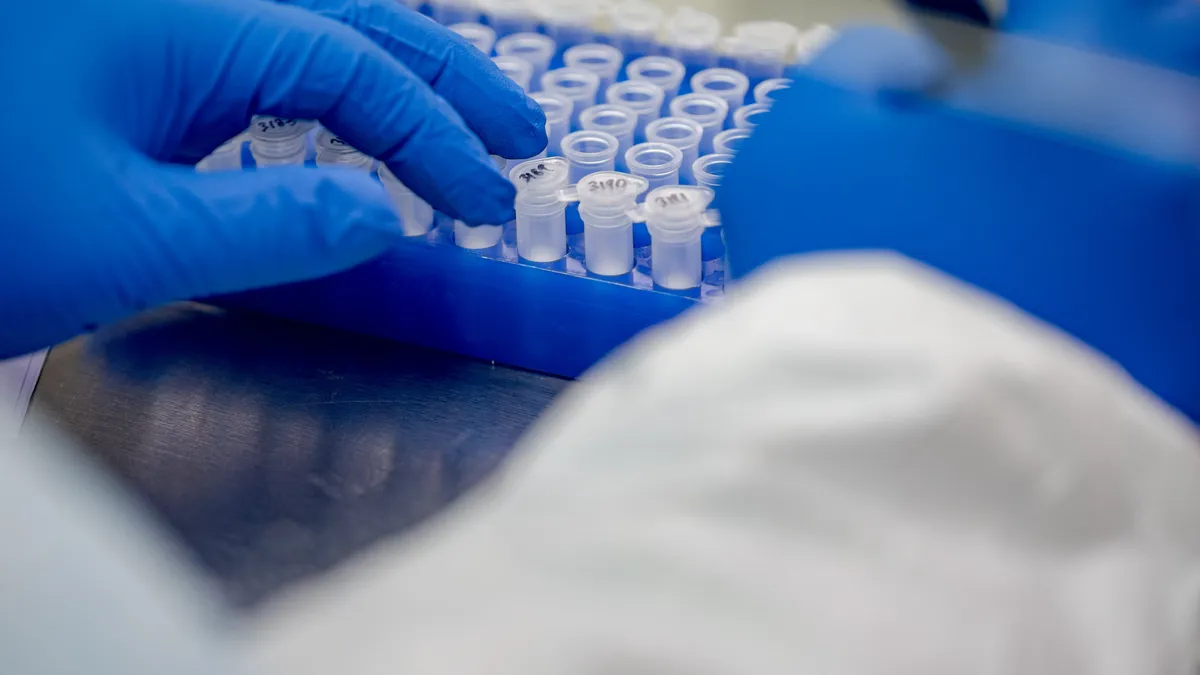

In mid-May, the small Christian university announced it had partnered with Helix Diagnostics, a Michigan-based clinical laboratory, to secure 5,000 tests for the fall. Most will be used to screen its roughly 4,000 constituents, including nearly 3,600 students, upon their return to campus. The remaining kits will be kept in reserve for additional testing of individuals at greater risk of exposure to the virus, such as student-athletes and nurses in training. (Le Roy declined to disclose how much the school is paying for the tests.)

As of mid-June, two-thirds of the roughly 970 colleges tracked by The Chronicle of Higher Education were planning to resume in-person instruction come fall. But doing so will depend in part on institutions' ability to conduct viral testing on at least a sample of their population, though some schools say they're committed to screening everyone. Boston University, for example, stated in late May that it plans to independently test its 40,000 faculty, staff and students on a regular basis, charging an on-campus research lab with assessing the samples. The University of California, San Diego, plans to do something similar, "broadly" testing its campus members on a "recurring basis."

Whether to test isn't the question. It is inevitable that campus constituents will contract and expose others to the coronavirus, according to the American College Health Association (ACHA). The pandemic is expected to worsen, and the virus could crop up at some U.S. campuses as the country reopens its economy and racial-justice activists take to the streets.

Colleges should instead consider who needs to be tested and how frequently, said the epidemiologist Craig Roberts, a University of Wisconsin–Madison professor emeritus and member of the ACHA's COVID-19 task force. While Roberts is confident tests will be widely available come fall, some experts worry about shortages. Whether colleges have the resources to screen everyone on campus is also unclear, as is whether it's worth doing so.

Unlike Boston University and other large research institutions, few colleges can perform testing on their own, Roberts said. And partnerships like the one Calvin worked out can be hard to come by at a time when the demand for such services is so high.

The cost of testing

Institutions that intend to screen everyone will need to ensure people can segregate themselves until they're cleared or no longer infectious, Roberts said. They'll also need to test regularly. Otherwise, he argued, "what's the point?"

The tests can also be expensive and labor-intensive, requiring far more investment than does installing plexiglass partitions, for example. According to Roberts, kits that use polymerase chain reaction technology — what he calls the "gold standard" — cost roughly $100 per person, though colleges can get discounts for buying in bulk. (The University of Wisconsin System could spend some $20 million to test all students, faculty and staff once as part of its reopening plan, according to early estimates.)

Labor makes up the bulk of the tests' costs. For example, colleges may need to pay people to collect the samples, process and transport the specimens, and sanitize the facilities. The testing machines, meanwhile, can cost as much as $100,000 a pop, Roberts said, accounting for depreciation and maintenance. Other elements, such as protective equipment and contact tracing, add to the financial burden.

Many of the available tests are also imperfect, Roberts added. And even institutions that manage to screen students and employees using both diagnostic tests (which assess for the active virus) and antibody tests (which determine whether someone had the virus) will struggle to gauge whether they've achieved herd immunity. (Colleges for the most part are focused on providing diagnostic testing.)

The ACHA has refrained from formally recommending the practice to colleges, as has the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But experts stress that colleges seeking to reopen their campuses in the fall will at least need to test people who demonstrate symptoms or have knowingly been exposed to the virus.

Colleges will invariably struggle to ensure full-scale social distancing on campus, where thousands to tens of thousands of students may learn, dine, exercise, live and even travel together. What's more, students at residential institutions often live alongside peers who hail from areas with varying transmission rates.

Not a 'panacea'

Absent sufficient mass-screening resources, Roberts suggested colleges focus on individuals with symptoms or who say they've been exposed to the virus, testing and then isolating them as soon as possible. While institutions are still developing their policies, some are rolling out online portals where students and employees may be required to share health and situational updates. Ohio's Clark State Community College has developed a checklist outlining the criteria students and employees need to satisfy before returning to campus.

"If somebody isn't feeling well or their temperature is above (100.4 degrees), they're asked to stay home and, if they present symptoms, to contact their health care provider and get tested," said Clark State President Jo Alice Blondin. The college's primary care health clinic is gearing up to support symptomatic individuals, including by referring them to local health providers equipped to test for the virus.

Cuyahoga Community College, also in Ohio, is working with the state's governor to set aside tests for the roughly 60% of students who it expects will participate in on-campus instruction in the spring of 2021. The college will take a triage approach to screening across its four main campuses, said President Alex Johnson, who chairs the board of the American Association of Community Colleges.

In the event tests are in limited supply, the school will concentrate resources on students who have symptoms or are in programs that require close contact with other individuals, such as nursing, dental hygiene and physical therapy. The college may also limit entry points to buildings to ensure they can take the temperatures of people passing through, referring those who are feverish to the local health department.

Ultimately, college officials acknowledge that testing alone won't protect their campuses from the virus. "We don't see testing as the panacea or the only thing you need to do," said Calvin's Le Roy. It's one of several strategies his campus is using to keep students and employees safe.

Blondin and Johnson echoed this thinking, emphasizing that their institutions will be offering mental health support to help students address the pandemic's economic and psychological toll, as most attend classes part time, work on the side and/or have children to care for.

"There is no playbook" for how colleges ought to handle COVID-19, Roberts said. "Nobody really knows what the best approach is."