This week, there has been a lot of talk about a story out of Tennessee in which Lipscomb University President L. Randolph invited African-American students to a dinner and served them collard greens and macaroni and cheese at a table set with cotton stalks.

The headlines focus primarily on the insulting nature of the stereotypes and the lack of cultural sensitivity. The real problem, however, isn’t what was served, or even the egregiously chosen centerpieces. It was that students thought they were coming to talk to the university leader about their experiences on campus, but instead were given little opportunity to speak while being subjected to cute personal anecdotes about the president and his family. One can’t help but note that if the president had ever actually had a listening session with these students, who make up only 7% of the campus population, he might have been able to avoid the missteps that are now the topic of conversation across the country.

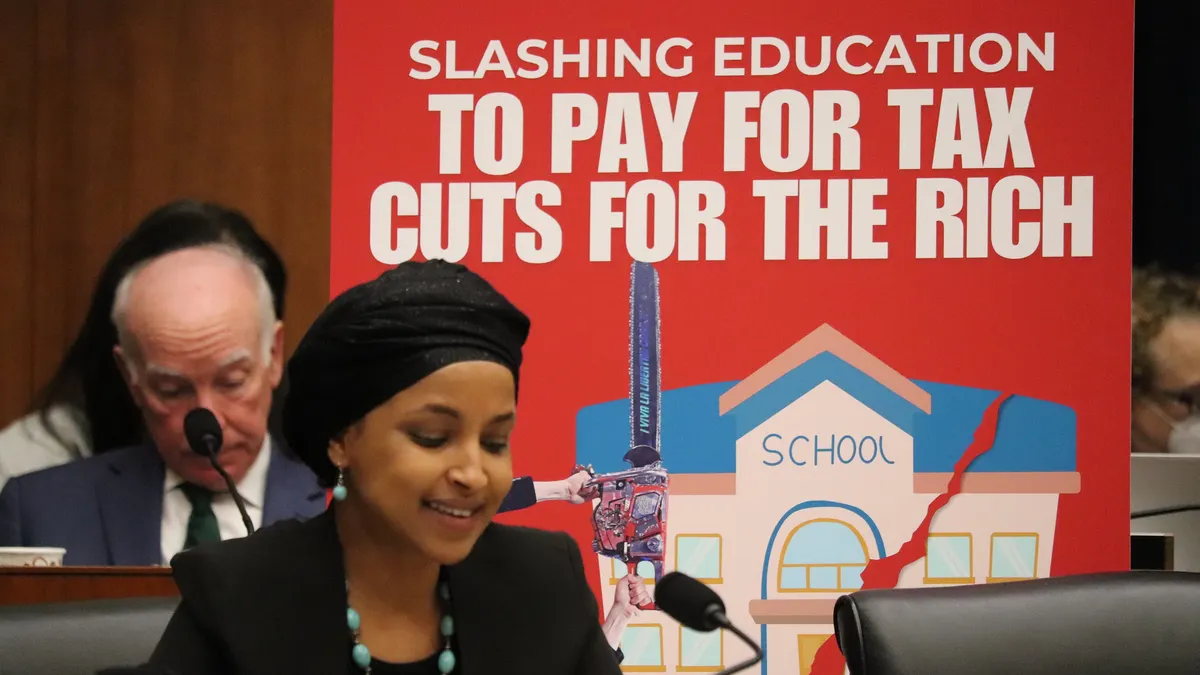

There were also questions raised about the institution’s financial commitment to supporting diversity initiatives, which is something that has come up in multiple conversations, especially discussions around supporting student success initiatives on campus. This is particularly important, because, as former U.S. Secretary of Education John B. King pointed out in a panel at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Annual Legislative Conference yesterday, “the reality [is] today, the majority of the students who are in our public schools are students of color. If we fail as a society to educate low-income students and students of color, we have no [educated populace and] we fail our democracy.”

A student takes an instagram photo of the table setting at the event.

“This is not your ordinary school year,” King said. “When I was a teacher and a principal, I loved the start of the school year, because [it gave you a clean slate]. You hadn’t made any mistakes yet. … But this year, our kids come back to school seeing the KKK and Nazis march across a college campus. Some of our kids come back in the face of a travel ban … some of our kids and their families come back to school worried that they may be deported.”

In other words, the current political and social climate in this country requires that campuses give more than lip service to genuine diversity efforts on campus. And not just because it’s nice to make students feel welcome and feel supported, but because the changing pipeline of students coming in means campuses will either have to get this right before those students arrive, or continue to grapple with missing enrollment targets — a recent survey from Inside Higher Ed and Gallup found only 34% of institutions met their enrollment targets this year. This means everyone else is struggling to make budget (except for HBCUs and other minority-serving institutions, several of which are actually experiencing record enrollment years).

Putting additional money into genuine diversity efforts means allocating resources to help boost graduation and retention among these students, as well. Scholarship support is not the only aid low-income students need. “We have the reality that African-American students who start college are 22% less likely to graduate than white students,” King said.

However, the types of supports which would make minority students more successful would actually benefit all students on campus — they’re simply good practice for any progressive institution hoping to remain viable over the next few decades.

Efforts such as hiring more advisors to help students identify the right courses early on, reimagining remediation to take a more co-curricular approach — realizing that many students of color are coming from K-12 schools which didn’t even offer the types of courses they’d need to succeed on campus. Kimberly Robinson, a professor of law at the University of Richmond, said on the same panel research shows “low-income children in concentrated poverty typically need 40% more resources to achieve on a level playing field with their peers.”

It’s also realizing that a conversation about “diversity” doesn’t only equal race. It’s making sure there are prayer and meditation spaces for students who may not feel comfortable utilizing a traditional chapel. It’s also reconsidering the amount of money spent on dorm amenities, which get passed on to students via rising tuition and fees, with a recognition that the “new normal” college student is likely older, likely already has a family and is probably not staying in the dorm. Perhaps a reinvestment in child care centers, which have all but disappeared from the higher ed landscape, would be a better allocation of funds than rock climbing walls in the student center.

The bottom line is university leaders are increasingly proving out of touch with what their constituents need, and even want. But there are a few examples of presidents who “get it” and have realized that simply asking people what they want can go a long way. At Goucher College, President José Bowen found asking students what they wanted in new buildings not only helped retain current students, it brought new students in. And University of Dayton President Eric Spina opened up his strategic planning input sessions to Facebook Live to allow as many constituents as possible to comment.

But overwhelmingly, at least if the headlines are any indication, institutions are not putting up the commitment — either financial or time — to learn their student populations and make the necessary adjustments. And that is why we have been talking about higher ed in crisis for the last few decades.