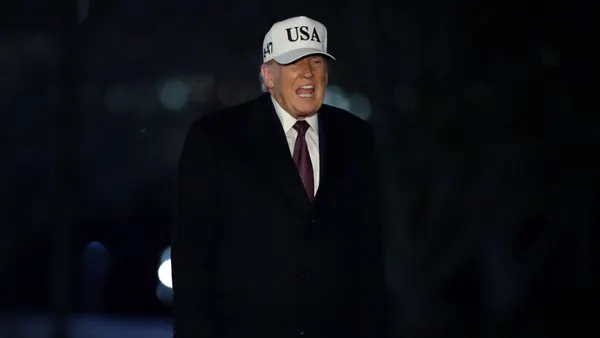

Since President Donald Trump retook office, the U.S. Department of Education has launched investigations into several high-profile colleges over their compliance with Section 117, a decades-old law that was largely ignored until 2018.

The law — part of the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act in 1986 — requires colleges that receive federal financial assistance to disclose contracts and gifts from foreign sources worth $250,000 or more in a year to the U.S. Department of Education.

In late April, Trump signed an executive order charging U.S. Education Secretary Linda McMahon to work with other executive agencies, including the U.S. Department of Justice, to open investigations and enforce Section 117. The order also explicitly ties compliance with Section 117 to eligibility for federal grant funding and directs McMahon to require colleges to disclose more specific details about their foreign gifts and contracts.

However, complying with the law is difficult and time-consuming for colleges given the challenges they face collecting the needed data and uploading it to the Education Department’s system, according to higher education experts. That means universities must take steps to ensure they are complying, such as dedicating a staff member to meet the law’s requirements, they said.

Failing to properly do so could put colleges in the crosshairs of the Trump administration and potentially cause them to miss out on federal grants, as higher education experts speculate the executive order will be used as another tool to target institutions’ funding.

“The Trump administration has it out for American higher education, particularly those they have branded elite institutions,” said Jeremy Bauer-Wolf, investigations manager on the higher education program at New America, a left-leaning think tank. “Section 117 is another cudgel for them.”

The history of Section 117

After Section 117 was enacted nearly 40 years ago over concerns about foreign donations to colleges, it was never really implemented by the Education Department and went largely ignored, said Sarah Spreitzer, vice president and chief of staff for government relations at the American Council on Education. People just stopped thinking about the issue and didn’t pay attention to it, she said.

However, concerns in Congress grew in 2018 when then-Federal Bureau of Investigations Director Christopher Wray testified before a Senate panel that China was exploiting the open research and development environment in the U.S. and universities were naive to the threat.

Proactively monitoring Section 117 and investigating disclosures was seen at the time as a way to “mitigate malign and undue foreign influence,” a Congressional Research Service report released this past February stated.

Following the hearing, the first Trump administration “really started making a show of Section 117,” said Bauer-Wolf.

Between 2019 and 2021, the Trump administration opened investigations into prominent institutions such as Harvard University, Georgetown University, Cornell University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Yale University. The administration was more focused on enforcing compliance through investigations than working with colleges to help them understand what the law required, said Spreitzer.

That had a “chilling impact on our institutions,” said Spreitzer. Colleges had a lot of questions about Section 117 reporting that went unanswered because they “were worried that if they called the Department of Education, they would be hit with an investigation.”

The investigations led colleges to report $6.5 billion in “previously undisclosed foreign funds,” according to Trump’s executive order.

When the Biden administration took over, Education Department officials moved enforcement of Section 117 from the Office of the General Counsel to Federal Student Aid. The Biden Education Department also closed several investigations launched under the Trump administration, and it did not open any new ones.

Trump, in his executive order, alleged the Biden administration “undid” the investigatory work completed during his first term. But those investigations had been going on for several years, so it’s unclear whether those probes should or should not have been closed, said Spreitzer.

Today’s enforcement landscape

Since retaking office, the Trump administration has opened Section 117 investigations into several colleges, including the University of Pennsylvania and the University of California, Berkeley, and it has reopened a probe into Harvard University. The Education Department said it needed to verify whether Harvard was complying with the law and with a December 2024 agreement that ended an investigation launched in February 2020 during Trump’s first term.

In the agreement, Harvard said it would submit amended disclosure reports for gifts and contracts received between 2014-2019. But when reopening the investigation, the Education Department said it believed Harvard made inaccurate disclosures, including for the amended reports.

“Unfortunately, our review indicated that Harvard has not been fully transparent or complete in its disclosures, which is both unacceptable and unlawful,” U.S. Education Secretary Linda McMahon said when announcing the latest probe in April.

As part of its new investigation, the administration asked Harvard for information regarding foreign students who were expelled, including the research they conducted, and “all temporary researchers, scholars, students and faculty who are from or affiliated with foreign governments.”

It also asked Penn, among a host of other things, for all tax records since 2017. In addition, the department requested the names of contractors or staff who assisted international students or were involved in the university’s regulatory compliance with the federal Foreign Government Talent Recruitment Program — referring to foreign governments' initiatives to recruit science and technology students and professionals.

“They are asking broader questions that go beyond the scope of Section 117,” said Spreitzer.

The threat of penalties, meanwhile, is all too real for universities on various fronts. The Trump administration has tried to compel universities to roll back their diversity, equity and inclusion efforts and has paused or terminated federal grants to universities such as Harvard, Princeton University, Northwestern University and Cornell University as it investigates antisemitism and civil rights allegations on their campuses.

Bauer-Wolf said he fears the Section 117 executive order will be used as another “political tool, almost as a shortcut to yanking colleges’ funding.”

“It will be another avenue that the administration can claim that colleges are not following the law, when in fact, this is a law I don’t think anyone had any recognition or compliance with,” he said.

“I really think there are legitimate uses for Section 117,” said Bauer-Wolf, adding that it's unfortunate the Trump administration and Republicans have "chosen to politicize it — instead of actually trying to find policy that could protect American interests and campuses.”

The new executive order also ties compliance with Section 117 to the False Claims Act — a federal law that penalizes people who knowingly submit false claims to the government.

It’s not clear how the Education Department will use the False Claims Act to enforce Section 117 against individual college officials or professors, said Matthew Kennison, a partner at Kelley Drye, a law firm that represents clients in government Investigations and enforcement proceedings.

But the prospect that the False Claims Act liability could be tied to Section 117 reporting “creates risks to institutions due to its ambiguity and potential broad reach,” said Anne Pifer, managing director of research at consulting firm Huron, which provides risk management and compliance services to higher ed institutions.

“While there is a high degree of uncertainty on the details of enforcement, institutions should expect increased oversight and scrutiny,” Pifer said.

Navigating the landscape

To comply with Section 117 requirements, colleges should follow the Education Department's published guidance and other resources and, when necessary, seek more specific advice from the department, said Kennison.

But reporting foreign gifts and contracts to the federal government is difficult and time-consuming, said Spreitzer.

An FSA reporting portal allows institutions to upload their Section 117 disclosures. Yet, according to Spreitzer, there’s no way for an institution to upload a spreadsheet listing all of their gifts and contracts.

“They have to go in and enter each gift or contract individually,” said Spreitzer. “For a large institution, it can take several days.”

Then, if an institution makes a mistake, there’s no phone number to call at the Education Department, said Spreitzer. The Biden administration set up an email address, but it's unclear if it is being closely monitored or responded to in a timely manner, she said.

“It will be another avenue that the administration can claim that colleges are not following the law."

Jeremy Bauer-Wolf

Investigations manager, New America

An Education Department official disputed Spreitzer’s characterization. Several full-time career staffers continuously monitor the email and respond to institutions' questions regarding Section 117 reports and reporting issues, the department official said.

Julie Hartman, an Education Department spokesperson, added in an email that the first Trump administration created the reporting portal in 2020 after years of “inadequate disclosures.” The Biden administration did not open any new Section 117 investigations, nor did it update the reporting website’s capabilities, she said.

“The Trump-McMahon Education Department is committed to reinvigorating Section 117 enforcement, including by improving the reporting portal in the coming months,” Hartman said.

A lot of large research institutions have carefully considered how to conduct their Section 117 reporting, Spreitzer said. But it requires “a whole campus effort to be aware of this requirement and to make sure you’re reporting that information twice per year,” Spreitzer said. She worries about the smaller, under-resourced institutions.

Those smaller institutions should designate a single point of contact to conduct the needed due diligence and make decisions on foreign sources that should be reported, Pifer said. And someone should be responsible for consolidating data sources and preparing and verifying the institution’s report, she said.

“Identifying a single point of conduct can minimize the need to train multiple offices on conducting complex reviews and help ensure data integrity,” Pifer said.

Such gifts or contracts are often found in university offices overseeing advancement and alumni relations, research, administration, procurement, bursars, and global affairs, Pifer added. Colleges should create a standard operating procedure or policy to identify and validate the sources of such gifts and contracts, and they should regularly review their gift acceptance and naming policies, she said.

But that work requires buy-in from the key stakeholders involved in collecting that data, she said.

“It is essential for institutions to establish sound practices and methodologies that will be robust and defensible in audits or investigations,” Pifer said.

Compliance through investigations?

The landscape for Section 117 compliance may only get tougher for colleges. The House recently passed a bill, called the Deterrent Act, that would add new reporting requirements to Section 117 and reduce the reporting threshold for foreign gifts and contracts from $250,000 to $50,000.

The bill would also require institutions to get a waiver before entering into a contract with a country “of concern,” which includes China and Russia. They would also have to report all gifts from countries of concern.

Currently before the Senate’s education committee, the bill would also introduce penalties for noncompliance, ranging from fines of $50,000 to losing federal financial aid.

Numerous higher education organizations have opposed the measure. including ACE, arguing it would significantly impede critical research activities and duplicate interagency efforts. The organizations, in a March 25 letter to House leaders, added the Education Department’s expanded data collection was “problematic” and wouldn’t ensure that "actual national security or foreign malign influence threats" are addressed.

“It is essential for institutions to establish sound practices and methodologies that will be robust and defensible in audits or investigations."

Anne Pifer

Managing director of research, Huron

Brandy Shufutinsky, director of the education and national security program at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a conservative research institute, suggested that nonmonetary penalties be considered for colleges that don't comply with Section 117.

For instance, they could be blocked from granting degrees, have their accreditation reviewed or see their nonprofit status be rolled back. Shufutinsky also recommended implementing a lower reporting threshold and being specific on which departments, professors or centers receive foreign funds and for what purpose.

Trump’s executive order on Section 117 is needed because “foreign funding in the US education system can contribute to foreign influence at those universities,” Shufutinsky said.

Still, the Trump administration’s focus on launching Section 117 investigations, instead of helping institutions with compliance, will make it harder for institutions to ask the Education Department whether they are actually reporting something correctly, said Spreitzer.

“The Trump administration seems to be again, trying to drive compliance through investigations," said Spreitzer. "I think that chills our campuses from actually asking questions.”

Disclosure: Jeremy Bauer-Wolf was a reporter on Higher Ed Dive from 2019 to 2023.