Online learning in higher ed turned into the Wild West in 2012, and the Internet remains abuzz with articles announcing the demise of the campus as we know it and hyping the most important education technology in 200 years.

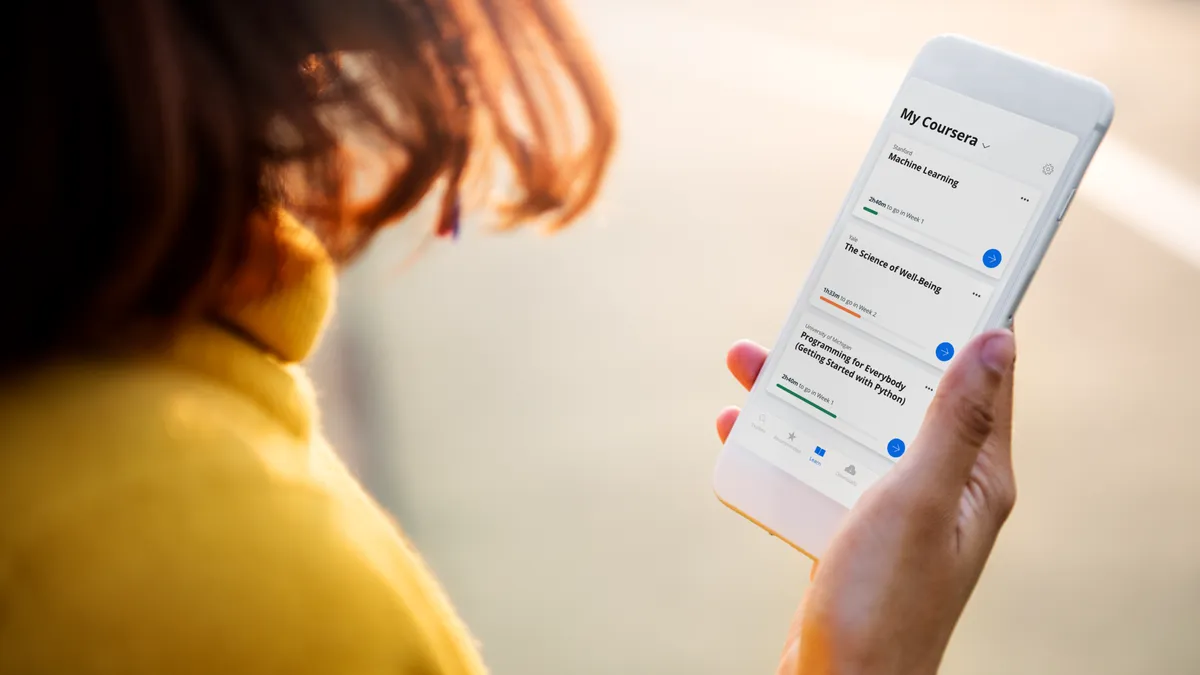

Massive open online courses, or MOOCs, as they are more commonly referred to, are hot in education right now. While the appeal of the acronym is questionable, the appeal of the idea is not — a free education for all, anywhere in the world with online access. Professors at prestigious universities host reviewable online lectures and curate videos, content and activities for their students. Users can tap into Ivy League-quality instruction on their own time, at their own pace and with little to no cost.

If it sounds too good to be true, that's because the hype has yet to match the reality. While MOOCs are already being touted as the solution to age-old problems in education, they have yet to solve seemingly simple problems, such as producing a sustainable business model and evaluating student performance in a meaningful way.

2013 is going to be a pivotal year for MOOCs. But before they can truly take advantage of the international marketplace and change education for good, the massive free offerings need to answer these eight questions:

1. IS THERE A MOOC BUBBLE ABOUT TO POP?

Universities, start-ups and education innovators must quickly decide whether to hop on the MOOC bandwagon or not. On one hand, MOOCs are being touted as the biggest breakthrough in education in the last 200 years. On the other, MOOCs could be a bust in which the concept never lives up to reality. In the next year, many educational institutions will gamble on their futures, negotiating between the risk of being left behind in a newly reshaped field of education and the risk of being outperformed in an extremely competitive market with low-to-no profits.

2. WHERE WILL THE MONEY COME FROM?

The inherent appeal of MOOCs is the emphasis on free education. However, MOOCs need money in order to sustain themselves. Until now, MOOCs have survived through multi-million-dollar grants and the altruism of educators, who are typically already salaried professors at prestigious institutions.

So far, a few promising alternative ideas have been proposed — charging for certificates, paid tutoring, recruiting services, networking events, in-MOOC advertising, selling textbooks and the Radiohead Payment Model. As MOOCs gain prevalence and decrease the need for our current institutions, MOOCs must figure out how to create sustainable business models for the future without compromising the principles that made them so popular in the first place. For free or for-profit — pick your poison.

3. HOW SHOULD THEY BE SUPERVISED?

Charles Severance, a professor at the University of Michigan, tracked the presence of cheating in his Coursera class, Internet History, Technology and Security, and, rather encouragingly, suspected only 20 students had cheated out of the 6,000 total that took the test. However, it is inherently much easier to cheat in an online course than in a physical classroom, and as MOOCs inch toward accreditation, the problem is becoming increasingly important.

While many MOOC providers currently operate on an honor code, some of them are now experimenting with site-based testing, both live and remote webcam monitoring, browser lockdowns, keystroke pattern recognition software and plagiarism detection software. MOOC providers must now negotiate between the practicality of solving the cheating problem and the ideal of learning for the sake of learning.

4. SHOULD MOOCS HAVE GRADES?

Or should they not grade at all? MOOCs currently have no established assessment methodology. The very concept behind MOOCs — that is, their ability to reach an unlimited amount of students — makes it rather difficult for professors to individually grade their students, and increasingly so as MOOCs gain popularity.

Grading varies from MOOC to MOOC—some rely on peer-to-peer assessment, some on machine grading. As MOOCs are being considered for accreditation, providers will weigh the unpredictability of peer grading, the inflexibility of machine grading and the uncertain implications of not grading at all.

5. BADGES, CREDITS OR DEGREES?

A college degree varies in value depending on who you talk to. MOOC badges, as they are called, are no different. While the American Council on Education considers accrediting MOOC providers, providers must choose between maintaining an alternative credentialing system or adjusting to the already established system.

Should MOOCs wait for employers and students to buy in? Or should they buy in themselves? While online courses are offered for credit at some universities, the San Francisco startup Degreed wants to create a digital diploma evaluating users' education for graduates of accredited programs and MOOCs alike.

6. COMPETITION OR COLLABORATION WITH UNIVERSITIES?

MOOC providers must decide whether to partner up with traditional schools to provide a higher-grade blended learning experience or offer a completely different and rival service which may spell the end of the campus-based education as we know it. The answer is not so black-and-white.

While third-world universities simply cannot compete with the free learning MOOCs provide, the world's most prestigious institutions have been integral in giving rise to MOOCs. Coursera, an eminent MOOC provider, is partnered with 33 prestigious universities while edX, another eminent MOOC provider, was created by Harvard and MIT. Certain schools, such as Stanford University's graduate programs, are already integrating online learning into their curriculums.

7. HOW WILL MOOCS TEACH STUDENTS WHO LEARN DIFFERENTLY?

The obvious advantage of MOOCs is their capacity to reach a nearly unlimited audience; the equal and opposite disadvantage is the loss of a customized learning environment. A substantial criticism of MOOCs is that the detached online format allows students to dropout without notice. Students who cannot self-regulate their learning may need individualized guidance, while students with learning disabilities and special needs may require personalized learning processes.

Experts argue MOOCs may give rise to the "McDonaldization" of education and that online learning should not limit itself to the largest possible scale. Donna Randall, President of Albion College, argues that students learn better in smaller-scale settings in which students interact with their instructors. In the next year, MOOC providers must negotiate between homogenized content for all and a learning-style-specific approach.

8. RECREATE THE CAMPUS EXPERIENCE?

One of the hugely touted advantages of brick-and-mortar institutions, and a major attraction for prospective students, is the so-called college experience. While grassroots meet-ups have been around since the beginning, MOOCs are facing demand to complement their online classes with in-person interaction. Peter Scott, director of the Knowledge Media Institute at the Open University, the largest online university in the UK, believes that online learning providers should invest in physical spaces to match the virtual spaces.

As MOOCs become increasingly popular, will providers create places for students to study, learn and live together?

Would you like to see more education news like this in your inbox on a daily basis? Subscribe to our Education Dive email newsletter! You may also want to read this list of 5 ways online learning is disrupting education.