The House Committee on Education and Workforce voted Tuesday to advance a wide-ranging higher education bill that would reduce eligibility for Pell Grants, roll back Biden-era regulations, and put colleges on the hook for loans their former students don’t pay off.

Committee Republicans say the plan would shave over $330 billion from the federal budget. The higher education bill is part of the House’s broader plan to cut $1.5 trillion from the budget to partially offset the cost of Republican priorities, including extending tax cuts enacted during President Donald Trump’s first term. The tax cuts are slated to expire at the end of the year.

Tim Walberg, the Republican chair of the House’s education committee, cast the bill as a way to reform a broken student loan system, push colleges to lower their prices and help shrink the federal deficit. However, the projected savings are a long way from covering the expected $4 trillion price tag attached to the tax cut extension.

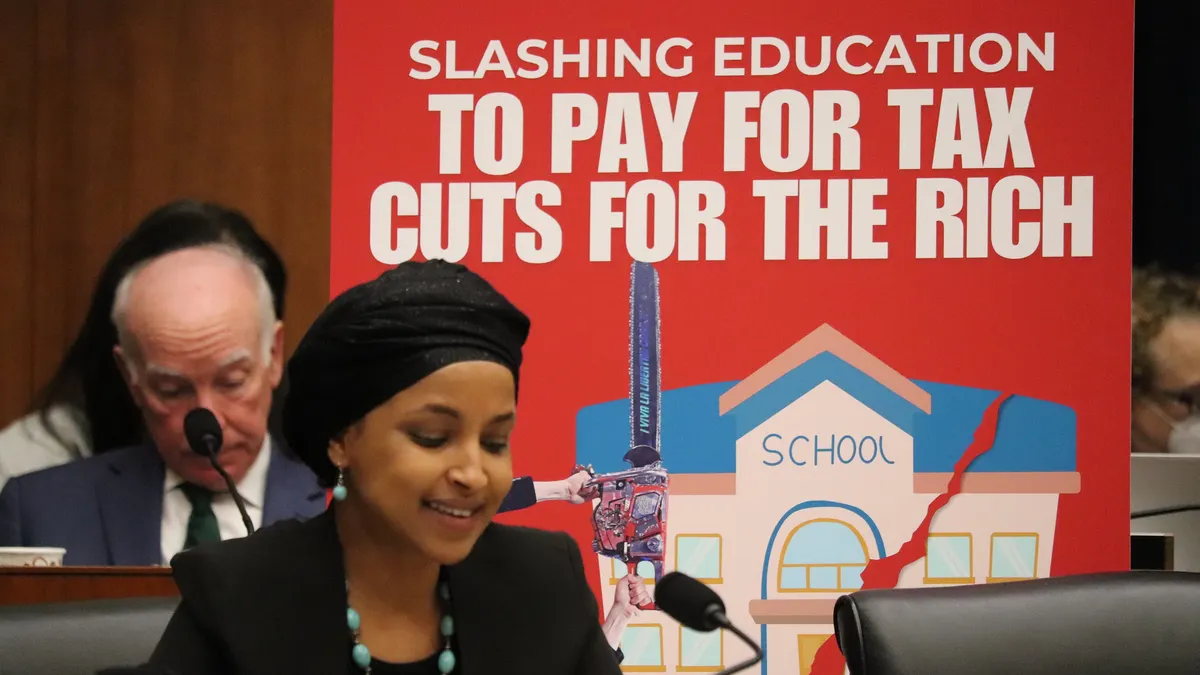

The bill advanced along party lines, with no Democrats voting in favor. Democrats slammed the proposals, arguing they would make it harder for low-income and working students to access federal student aid and for borrowers to pay off their loans.

“The reconciliation bill will cut access to higher education for students and also will shower the wealthy with massive tax cuts,” Rep. Bobby Scott, the committee’s top Democrat, said during Tuesday’s markup of the bill.

Some higher education groups have already come out in opposition to the sweeping changes. Six higher education groups, led by the American Council on Education, told Walberg in a letter Tuesday that they objected to many of the proposals, arguing the bill would impose “onerous financial penalties” on colleges and harm students.

The committee's vote puts the proposals on the path toward approval under a process known as reconciliation, which allows Congress to pass budget-related bills with only a simple majority versus the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster in the Senate. However, both the House and the Senate will need to agree on identical higher education provisions before they could become law.

What’s in the bill?

The legislation would make massive changes to federal student aid. For one, it would cap the aid students can receive each year to the median nationwide cost of attendance for students in their same program of study.

From fiscal 2026 to 2028, the bill would provide a total of $10.5 billion in additional funds for the Pell Grant program to address an expected funding shortfall. However, it would also require students to complete at least 15 credit hours each academic year to be eligible for Pell Grants — a change that critics say would disproportionately harm those who must balance their studies with work and parenting responsibilities.

The plan would also reshape the federal student lending system. Starting July 1, 2026, the U.S. Department of Education could not issue new Grad PLUS loans. It would also eliminate new subsidized loans, which provide students relief from interest while they are in college and for six months after they leave their institutions.

At the same time, the bill would cap total unsubsidized loans at $50,000 for undergraduate programs, $100,000 for graduate programs and $150,000 for professional programs. Moreover, students would have to exhaust their unsubsidized loans before their parents could take out Parent PLUS loans to cover remaining college costs.

Rep. Randy Fine, a Republican from Florida, argued that these moves would spur colleges to cut their prices to maximize their enrollment.

“The solution to the problem is not to double down on the status quo and giving people more debt, which creates more problems,” Fine said. “The better solution is to do what we propose to do in this bill, which is to cap the debt, which tells the universities what they can charge.”

However, Democrats argued Tuesday that these types of changes would make college more expensive for the most vulnerable students.

“The majority is actively choosing to make life more expensive and increase the national debt that they claim to care so much about,” said Rep. Lucy McBath, a Democrat from Georgia. “They are actively choosing to cut Pell Grants for the lowest-income students and families in this country.”

Scott echoed those comments, arguing that the proposal would leave students with fewer and worse options for financing their higher education.

“Most of the provisions targeted towards reducing federal student aid exacerbate the college affordability crisis by limiting the students’ access to Pell Grant and federal loans, and then pushing them to the only thing that may be left if they want to go to college — and that is predatory private loans,” Scott said.

Putting colleges on the hook

The bill would create what Republicans’ deemed “skin-in-the-game accountability” for colleges. Under the risk-sharing plan, institutions would have to reimburse the government for a share of their students’ unpaid federal loans, starting with those dispersed on or after July 1, 2027.

Many of the ideas in the legislation — including the risk-sharing proposal — are pulled from the College Cost Reduction Act, a wide-ranging Republican bill introduced in early 2024 to revamp higher education.

The act failed to gain traction outside of the House education committee, and Republican lawmakers would not have been able to overcome then-President Joe Biden's expected veto had the proposal gone further. Under Trump, however, the new legislation has a much better chance to become law if legislators vote along party lines.

Colleges would be penalized for making late risk-sharing payments — ultimately including the loss of their eligibility for Title IV federal student aid. However, the draft legislation also would create Promise Grants, which would provide additional funding that “rewards colleges for strong earnings outcomes, low tuition, and enrolling and graduating low-income students.”

A whopping 98% of colleges would be on the hook for risk-sharing payments, according ACE’s letter to Walberg. Even after considering the Promise Grants, ACE expects that three-fourths of colleges would see a net loss from the risk-sharing plan.

Republicans argued that this provision would incentivize colleges to lower their costs. But Rep. Suzanne Bonamici, a Democrat from Oregon, called the proposal “shortsighted.”

“It creates this perverse incentive for schools to shut down programs that prepare students for in-demand but underpaid careers like teaching or social work or public service fields,” Bonamici said. “Additionally, the proposal would create an incentive for schools to enroll wealthier students who are more likely to repay their loans at higher rates and minimize the risk to the institution.”

The draft legislation also targets the Biden administration’s higher education regulations. That includes eliminating the 90/10 rule, which requires for-profit institutions to receive at least 10% of their revenue from sources other than federal education funding.

It would also repeal the gainful employment rule, which requires career education programs to prove graduates earn enough to pay off their student loans. At least half of their graduates must also earn more than workers with only a high school education in their regions, under the rule.

And the bill would repeal the Biden administration’s version of the borrower defense to repayment regulations. The rule, which makes it easier for students defrauded by their colleges to get debt relief, has already been temporarily blocked by an appeals court and is set to be reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

However, the Supreme Court put the case on hold after the Trump administration requested a pause to review the “basis for and soundness” of the rule.