U.S. colleges hosted nearly 1.2 million international students in the 2024-25 academic year — a 4.5% increase from the previous year and an all-time high — according to the annual Open Doors report from the Institute of International Education and the U.S. Department of State.

But those numbers are poised to fall this academic year. In a preliminary fall survey of 825 colleges, Open Door researchers found that international enrollment declined 1% at those colleges in the first half of 2025-26, driven by a 12% drop-off in graduate students.

This survey could serve as a warning light for international enrollment under the Trump administration, which has attacked foreign students and moved to tighten the visa programs that allow them to study at U.S. colleges.

The Open Doors survey further found that new international enrollment decreased 17% in fall 2025 at polled institutions. Over half of those colleges, 57%, reported a decline in these students.

Growth for some programs, losses for others

International students — who often pay the full sticker tuition price — are a crucial segment of the higher education sector, particularly at a time when the number of high school graduates in the U.S. is expected to drop and colleges are operating on increasingly thin margins. They are especially important to smaller colleges that rely heavily on tuition revenue.

International students accounted for 6.1% of U.S. college enrollment last academic year, the report said. And they contributed nearly $55 billion to the U.S. economy in 2024, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce.

However, the number of international students who enrolled at a U.S. college for the first time declined 7% in fall 2024 compared to the previous year — the first decrease since the pandemic. A sharp 15% drop in new international graduate students drove the loss, even though new international undergraduates grew 5% year over year.

In 2024-25, over 488,000 international students pursued a graduate degree in the U.S. That's down 2.7% from about 502,000 the previous year and follows three years of growth.

Inversely, international undergraduates grew 4.2% to just over 357,000 students, "marking the first significant increase" since the pandemic, the report said.

Open Doors also reported a major increase in the number of international students participating in the Optional Practical Training program. Through the program, student visa holders can stay in the U.S. and work in their field of study for up to three years after graduating.

In 2024-25, more than 294,000 international students took part in OPT — up 21.2% from the previous year.

In addition to the 1.2 million international students in the U.S., another roughly 17,000 enrolled at U.S. colleges online and studied from outside the country.

Federal attacks on international enrollment

Since President Donald Trump retook office in January, his administration has sought to limit international enrollment. For instance, a U.S. Department of State spokesperson said in August that the agency had revoked more than 6,000 visas for international students already studying in the U.S.

Another attempt came via a proposed deal with research institutions.

The Trump administration has offered nine colleges preferential access to federal grants in exchange for enacting several wide-ranging policies to forward its higher education agenda. One of the conditions is capping international student enrollment to 15% of the institution’s undergraduate student body. None of the nine colleges initially offered the deal have so far taken it, though Trump has opened up the deal to all institutions.

The Trump administration may be making headway through other deals.

Columbia University, in New York, hosted almost 21,000 international students in 2024-25, according to Open Doors.

But the private research institution signed an unprecedented deal with the Trump administration this year that, in part, requires it to decrease its financial dependence on international students and ask applicants from other countries about why they want to study in the U.S.

Some colleges are turning to flexible policies to protect their international student enrollment, according to Open Doors’ fall 2025 survey.

Nearly three-quarters of respondents, 72%, said they were offering international applicants the option to defer to spring 2026. More than half, 56%, extended that offer to fall 2026.

Colleges also reported looking into new markets.

More than half of surveyed college leaders, 55%, reported prioritizing undergraduate outreach to Vietnam, where 14.4% of the population is between the ages of 15 and 24. About half, 49%, said the same of India, where 17.1% of residents fall into that age range.

Where international students come from

India continues to send the most international students to the U.S., and the number is steadily rising, Open Doors found. In 2024-25, just over 363,000 Indian students studied in the U.S., up 9.5% from about 331,000 the year before.

The U.S.' second biggest source of international students is China, with almost 266,000 Chinese students enrolling here. But that represents a 4.1% decline from over 277,000 international Chinese students in 2023-24, continuing a multi-year drop-off that began with the pandemic.

The Trump administration has focused much of its international student crackdown on China, though messaging has been inconsistent.

In May, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said his agency would “aggressively revoke visas for Chinese students," particularly for those “with connections to the Chinese Communist Party or studying in critical fields."

But his 60-word announcement provided few details, and it no longer appears on the U.S. Department of State website. Trump later appeared to walk back Rubio's statement, further muddying the waters.

Trump again appeared to defend Chinese students on Fox News last week. "It’s good to have outside countries," he said when asked about international students at U.S. colleges.

Even with declining numbers, China still accounts for almost a quarter of the international students in the U.S.

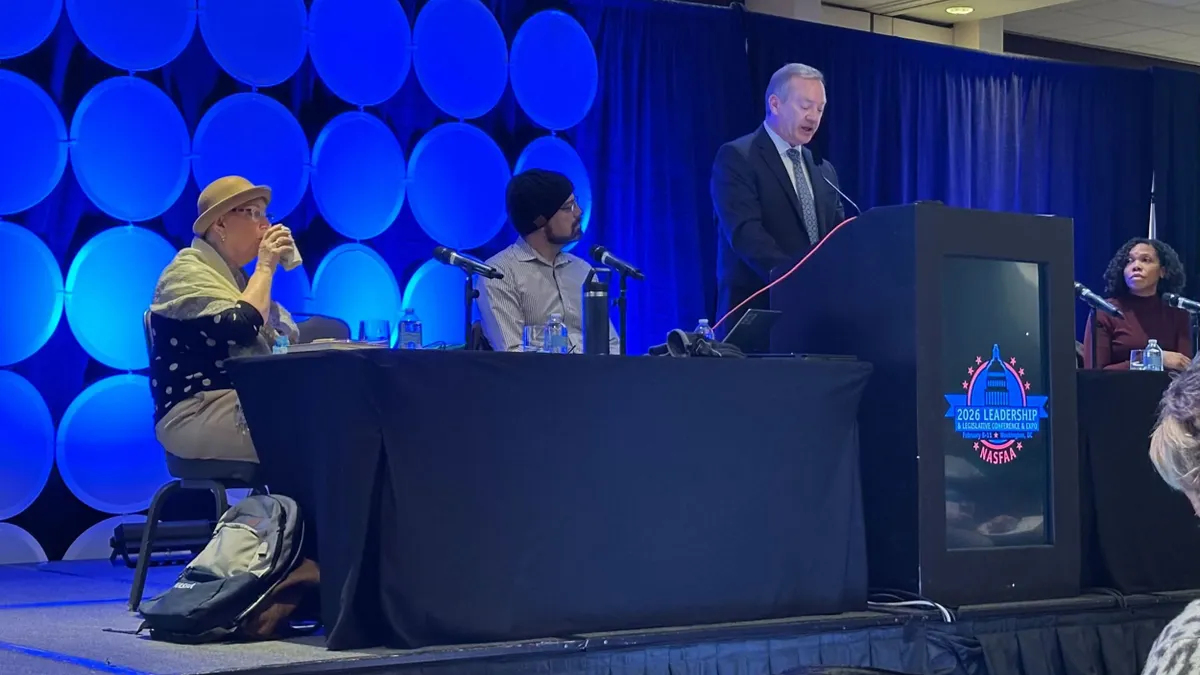

Colleges push back on proposed visa time caps

The Trump administration has also proposed capping how long foreign students can stay in the country to four years, regardless of their program. F visas typically allow international students to remain in the U.S. for as long as it takes to finish their studies.

Such a cap could disproportionately affect graduate students, who make up the majority of international students in the U.S. Students wishing to stay beyond four years would have to apply for extensions and undergo “periodic assessments” under the proposal.

The August proposal evoked immediate pushback from student advocates and higher ed groups. The administration received almost 22,000 comments at the close of the proposed policy’s feedback period on Oct. 27.

The University of Michigan — which has the 11th most international students of any U.S. college, according to Open Doors — argued that a four-year cap "does not align with the normal program completion times, particularly for large research universities." Doctoral programs, for example, typically take at least five years to complete, it said in its comment.

Boston University — with the 9th highest international student population — similarly urged the administration to withdraw the visa cap proposal.

"Disincentivizing international students and scholars from coming to the country could have long-term negative economic consequences should they seek out alternative destinations," it said in its comment. The university also raised concerns about the proposed cap putting an administrative burden on international students and harming their academic mobility.

Other institutions that opposed the proposal include Vanderbilt University, Brown University, the University of Pittsburgh, Drexel University, Johns Hopkins University, the Massachusetts State Universities Council of Presidents, and Minnesota State Colleges and Universities.