Editor’s note: The College Closure Files is an occasional column chronicling why institutions shuttered and what lessons higher education leaders can glean from those shutdowns.

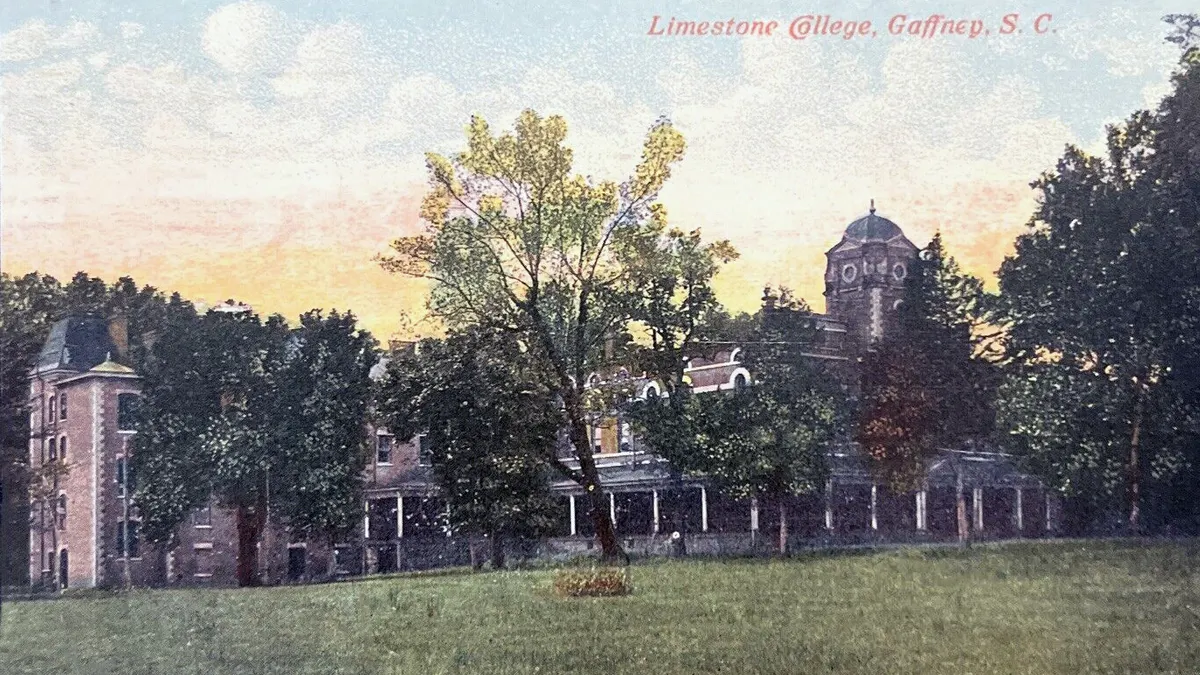

Limestone University graduated its final class this past spring after a last-ditch effort to raise enough money to stay open fell short. Founded in the mid-19th century, the South Carolina institution experienced financial tumult several times throughout its life, including when it closed temporarily during the Civil War-era.

Here’s a look at Limestone’s history and what went wrong in the end.

The early years

Limestone began its life as a Southern women’s college. In fact, it was likely South Carolina's oldest women's college and one of the oldest in the South.

Established by Baptist clergy on property once home to a resort at the bucolic Limestone Springs, the institution offered both religious and liberal arts instruction.

Over the second half of the 19th century, the college temporarily closed and the property changed hands.

Limestone University at a glance:

Founded: 1845

Closed: 2025

Location: Gaffney, South Carolina

Institution type: Four-year private nonprofit

Student body: 1,782 (fall 2023)

Mission statement: “Limestone University is committed to the liberal arts and sciences and to educating the individuals who will become tomorrow’s leaders, who will render meaningful service, and who will enjoy professional fulfillment as lifelong learners.”

It fell on troubled financial times during the Civil War as the institution’s leader at the time, William Curtis — son of Limestone’s co-founder — lent money to the Confederate government, according to an official college history. Curtis had no hope of being repaid after the South was defeated. Meanwhile, the wealthy planters who sent their daughters to the college also came into hard times following the war.

Earlier, when Limestone was shuttered for an extended period in the early 1860s, “splendid laboratory equipment” was carried off and destroyed while the property was unoccupied, though details of what exactly happened didn’t make it into the records, according to a history of the college published in 1937.

“You may say that Limestone is immortal. If anything could kill it, it would have been dead long ago.”

Harrison Patillo Griffith

Post-Civil War era leader of Limestone

Curtis was deeply in debt in the early 1870s — after his own loans to the Confederate government went unpaid — and sold the property. The new owners, Thomas Bomar and Charles Petty, reopened Limestone.

In the early 1880s, the institution was renamed the Cooper-Limestone Institute. By then, it was teaching courses in zoology, astronomy, political economics and many other areas. Collegiate tuition cost $25 per term in those days, less than what students at the time might pay for their art supplies and music classes. Board was another $62.50.

Limestone rose out of debt under new leadership in that period, and the institution attracted enough students to become self-sustaining.

“You may say that Limestone is immortal,” a college leader of the era said, a comment likely informed by the institution’s turbulent financial history up to then. “If anything could kill it, it would have been dead long ago.”

By the end of the century, the institution was renamed Limestone College. As its higher education ambitions grew, it leaned into its Southern identity. It built an architecturally ambitious history center named after Winnie Davis, a daughter of the Confederacy’s president and a symbol of “Lost Cause” historical narratives that mythologize the Confederacy and downplay slavery’s role in Southern secession and the Civil War.

The institution, in a course catalog from the early 20th century, called the historical center “a great department of a great college donated to the education of Southern Women.”

In 1930, the college began admitting men as commuter students. By the late 1960s, the institution was fully coed, with dormitories for men as well as women.

The college barred Black students from attending until the desegregation era. M.L. Annette Reynolds became Limestone’s first Black student and, in 1970, its first Black graduate. Half a century later, Limestone awarded Reynolds an honorary doctorate and named an endowment fund after her.

Later in the century, Limestone became a pioneer in serving nontraditional students and working adults.

In the 1970s, it created a program that allowed students to complete bachelor’s degrees entirely through evening classes. Two decades later, it created a “Virtual Campus” for instruction. In 2005, the college combined the Virtual Campus with its evening program as the basis of an online program.

“Providing higher education access to those needing it the most has been a proud theme throughout the history of Limestone,” the institution says on its website.

Over the 20th and 21st centuries, Limestone experienced alternating periods of relative stability in leadership and finances mixed with times of turbulence.

The institution had three presidents over the first roughly 65 years of the 20th century, and then eight presidents in the next 26 years — three of them on an interim basis. When Walt Griffin took over as president 1992, Limestone faced “dwindling enrollment, major financial deficits, and deteriorating buildings,” in the institution’s words.

But, according to Limestone's website, the college “not only recovered from the hard times of the 1980s, but also flourished during his [Griffin's] presidency until he retired in 2017.”

The institution changed its name to Limestone University in 2020 after adding master’s programs in business and social work.

Path to closure

In 2023, Limestone’s auditor raised doubts about the institution’s ability to continue operating, citing “a decline in enrollment and uncontrolled spending” during the previous two fiscal years. Limestone’s expenses had spiked 20% between fiscal years 2020 and 2022 to $46.2 million.

The university hired consultants to help stem its financial troubles. They recommended reducing its workforce, cutting underperforming programs, canceling satellite location leases, expanding online programs and launching a capital campaign to raise unrestricted funds.

Along with rising costs, the institution faced a shrinking student body. Between 2018 and 2023, Limestone’s fall enrollment cratered, declining 27% to 1,782 students. In that respect, the university faced struggles similar to many other small private liberal arts colleges.

The trouble ran even deeper, however. Gary Stocker, founder of College Viability, a data platform looking at college financial health and failure risk, points to the university’s dismal graduation rates. By fall 2023, Limestone’s graduation rate hadn’t cracked 40% for a decade, according to federal data.

“The first thing I always like to look at is graduation rates,” Stocker said. “These kinds of colleges are more tuition collection agencies — they're collecting tuition, and they're not graduating anybody.”

Then, Limestone’s financial struggles deepened even more. In 2023, the university secured approval from the state attorney general to remove restrictions on its endowment and began drawing millions from that fund to maintain its operations. Between fiscal years 2023 and 2024, Limestone’s net assets fell by more than $12 million, to $61 million.

“They had been robbing the endowment piggy bank to keep the lights on and meet payroll,” Stocker said. “You just can’t do that.”

College Viability data shows Limestone’s net tuition revenue declining since fiscal 2016 while its net income margin tanked after 2021. Expenses rose at the same time — growing over 10% in fiscal 2022 and 2023.

Unrestricted net assets — which Stocker describes as the essential financial value of the college — also collapsed after fiscal 2021. They fell from almost $25 million that year to roughly $1 million in 2023 before jumping to nearly $5 million the following year.

“The Limestones of the world will continue to close, because they chronically believe they can do it themselves. Don’t wait to have that merger conversation.”

Gary Stocker

Founder, College Viability

“More colleges than not have not had a decent post-pandemic recovery, and clearly Limestone fits that bill,” he said.

This past April, Limestone’s board of trustees announced that the 179-year-old institution needed an immediate infusion of $6 million in emergency funding or it would have to move exclusively online or shutter entirely. On Facebook, the institution said, “Please join us in praying for God’s guidance and strength in the days ahead.”

Days later, it announced a possible “financial lifeline” that could allow it to stay open. Officials offered scant details other than saying a “possible funding source” had emerged. Even with that newfound hope, Limestone President Nathan Copeland said the university would operate on the assumption that it would transition to online-only after the spring 2025 semester.

But before the month ended, Limestone officials called it: They announced the university would close permanently after the semester, despite having raised $2.1 million in a Hail Mary fundraising sprint.

“In the final analysis, we could not continue operations on-campus or online without a greater amount of funding,” board Chair Randall Richardson said.

What can we learn?

In the wake of Limestone’s demise, faculty issued a blistering assessment of its leadership during its final years and days.

In a written statement, faculty alleged that during his interview for the presidency, Copeland promised to turn the university’s finances around and communicate more with faculty on its financial condition.

“However, since his installation in the summer of 2024, the faculty have heard from him three times, and in each of those, he provided nothing but platitudes and vague allusions to ‘trying,’” they said. “We were still not informed of the dire state of our institution or its likelihood to be suddenly shuttered at a moment's notice.”

Faculty described a lack of information about the university’s financial condition from its leaders, whom they accused of mismanaging Limestone.

“The lack of effective governance and oversight from the Board demonstrates their total and utter incompetence and their drive to do nothing more than pad their own resumes,” the faculty said.

Their statement accompanied a no-confidence vote in the board and Copeland. Faculty also disinvited the trustees, Copeland and the university’s vice president from Limestone’s last-ever graduation ceremony.

"Once you have to take your savings and pay for your monthly expenses, you’re moving quickly to a point where your model is not going to be viable."

Chuck Ambrose

Senior education consultant, Husch Blackwell

Faculty anger is common amid sudden college closures. So are questions about what university leaders knew and when — and if closure could have at some point been avoided, or at least managed with more planning.

Stocker’s advice to college presidents looking at Limestone's experience: “Don’t wait this long.”

He pointed to the university's falling assets after 2021, its use of endowment funds during that time and other red flags that emerged well ahead of its closure. A hard look at negative financial signals could have led Limestone to seek a merger partner before it was too distressed for anyone to want to join with or acquire it.

“The Limestones of the world will continue to close, because they chronically believe they can do it themselves,” he added. “Don't wait to have that merger conversation. You may or may not move forward, but you want to have it today, so that you can least think that through.”

Dwindling endowment serves as a stark warning. When colleges start drawing from their endowment to pay the bills, they're likely already in deep financial trouble.

Institutions can scale down their expenses in some cases to meet new enrollment and revenue realities, but the market is sending signals through college closures that some won't even be able to do that, according to Chuck Ambrose, a senior education consultant with law firm Husch Blackwell who has served as chief executive at several colleges.

The most important action for colleges to take, Ambrose said, is to align their expenses with revenue. But some institutions have waited too long to do that, he said.

"Once you have to use your assets — once you have to take your savings and pay for your monthly expenses, you're moving quickly to a point where your model is not going to be viable," Ambrose said.