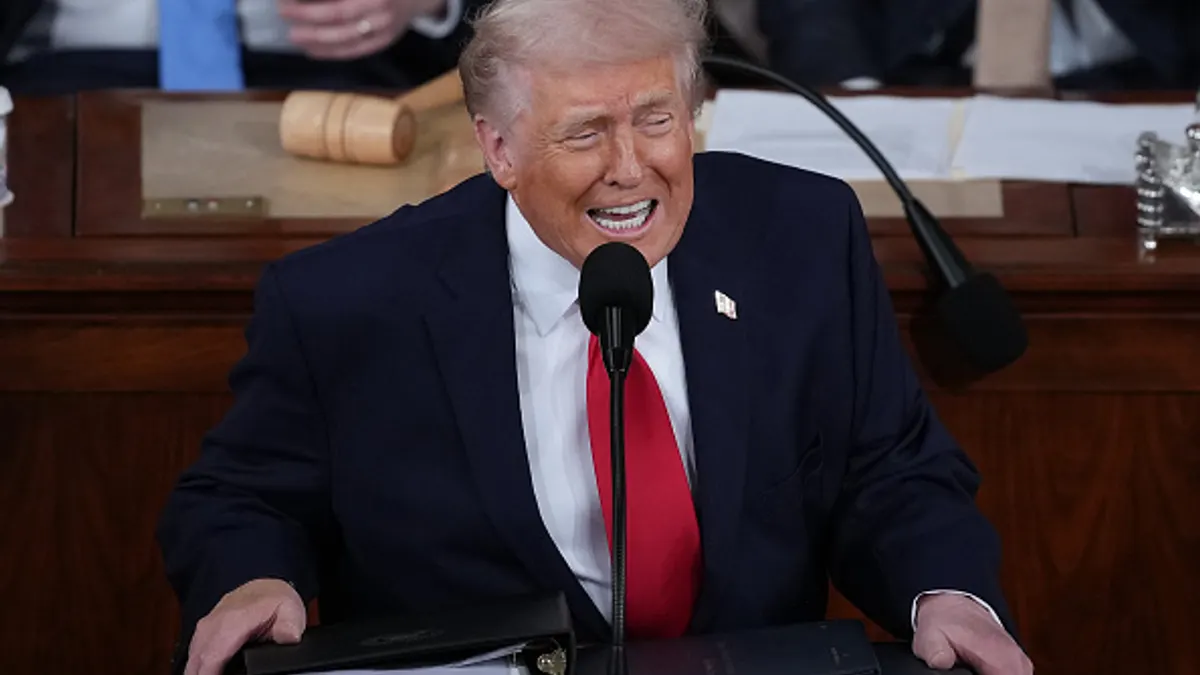

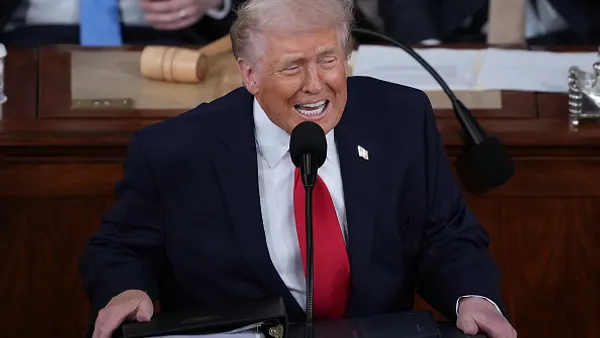

The Trump administration is at the center of many of the higher education world’s biggest lawsuits this year. There’s a simple reason for that: The administration’s actions and policies, if fully realized, would have a massive impact on the sector.

Immediately after President Donald Trump’s inauguration, his administration began aggressively using the levers of the federal government to reshape a higher education system that he has described as failing students and hopelessly left-wing.

Many of these actions were swiftly met with legal challenges. From rulings regarding attacks on research funding to diversity efforts, courts are playing a key role in determining the ultimate shape and effects of Trump’s policies.

Many cases are still working their way through the system, meaning much remains uncertain as the new year starts. Below, we’re rounding up some of the key lawsuits we’re watching this year, most of them involving Trump and his administration.

Harvard pushes back against Trump administration

Since Trump took office, his administration has opened probes into dozens of universities as it pursues policy changes at those institutions and, in some cases, monetary payments to the federal government.

But its pursuit of vast policy changes at Harvard University has been singularly aggressive even by the administration’s unprecedented standards. In April, the government froze $2.2 billion in research funding to Harvard after the Ivy League institution declined to adopt the administration’s sweeping demands to settle allegations that the university didn’t do enough to protect Jewish students from harassment.

Harvard sued the Trump administration over the funding freeze in late April. It later sued again after Trump’s government revoked the university’s ability to enroll foreign students, quickly winning a ruling to block that decision.

The Trump administration has also threatened Harvard's patent revenue and accreditation, among other moves.

In early September, U.S. District Judge Allison Burroughs, an Obama appointee, ruled against the Trump administration’s freezing of $2.2 billion of the university’s federal funding.

Burroughs found that the administration violated Harvard’s First Amendment rights, didn’t follow proper procedures when freezing the funds, and acted arbitrarily and capriciously.

In December, the administration appealed the ruling.

A White House spokesperson at the time maintained the administration’s claim that Harvard had allowed harassment against Jewish students to “run rampant” and said “the university will be held fully accountable for their failures.”

The ultimate direction of the case could have profound implications for a higher ed world trying to navigate the financial and legal perils of Trump’s moves.

The American Council on Education and 27 other higher ed organizations expressed that view in an amicus brief supporting Harvard. In it, ACE and the other groups described a diverse higher education system composed of a wide spectrum of institutions with varying missions independently governing themselves.

“The Administration’s actions reverberate far beyond Harvard and jeopardize the richness of this spectrum, which has long been one of our country’s greatest strengths,” the organization said in the June court filing. “The Executive Branch is not empowered to punish or, at the extreme, destroy any citizen or institution for refusing to accede to unlawful demands.”

Jon Fansmith, ACE’s senior vice president for government relations, told Higher Ed Dive in December that the worst possible outcome of Harvard’s legal battle would be a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the Trump administration’s favor.

Such a decision would set a precedent “where these kinds of actions — unquestionably contrary to what the law requires the administration to do — are somehow valid,” Fansmith said. “And if you establish that precedent, then that becomes an empowering tool for the administration to use the same model anytime, anywhere when an institution in any way displeases them.”

Harvard hasn’t been the only one to sue over the administration’s actions against the Ivy League university. Before Harvard launched its own legal challenge, the American Association of University Professors and its Harvard chapter sued the government, arguing that its actions against the university undermined academic and expressive freedoms.

AAUP has also filed lawsuits over similar Trump administration attacks against Columbia University and the University of California.

The judge overseeing the Columbia case said faculty lacked standing to sue over the administration’s demands on the university — a decision that the faculty group appealed. However, AAUP won standing and favorable rulings in the Harvard and UC cases.

“The judges said that the Trump administration cannot freeze federal funding based on unsubstantiated claims of antisemitism. That's just not allowed,” AAUP President Todd Wolfson told Higher Ed Dive in January.

Research institutions fight indirect cost caps

In early February, the National Institutes of Health said it would henceforth cap reimbursement rates for research overhead at 15%.

The move represented a radical policy change and potential financial bomb for many research universities, some of which have negotiated indirect cost rates with the government above 50%. Indirect costs include such things as building labs and running equipment for publicly funded research, as well as paying administrative staff who work on the projects.

NIH’s indirect cost cap quickly drew multiple lawsuits, including from attorneys general in over 20 states. In their complaint, the states that “without relief from NIH’s action, these institutions’ cutting-edge work to cure and treat human disease will grind to a halt.”

Major higher ed associations sued as well. ACE, Association of American Universities, and Association of Public and Land-grant Universities jointly filed a lawsuit.

In a statement at the time, the three organizations described NIH’s cap as a “self-inflicted wound” on the country that risked derailing research for disease cures and hollowing out the scientific workforce.

“Besides its devastating impact on medical research and training, the proposed actions run afoul of the longstanding regulatory frameworks governing federal grants and foundational principles of administrative law,” the groups said in February.

The courts agreed.

A federal judge issued a temporary restraining order barring NIH from instituting the cap as the cases played out. In April, the judge permanently blocked the indirect cost limit.

Despite the court setback, other agencies in the Trump administration followed NIH’s lead shortly anyway. The U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Defense all adopted similar indirect cost caps — and were swiftly sued. Federal judges have so far blocked the reimbursement limits at those agencies as well.

The cases are in various states of flux. An appeals court upheld the lower court’s block of NIH’s indirect cost cap. NIH has not said whether it will appeal to the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has appealed the rulings against the caps by the departments of Energy and Defense, while the NSF in September withdrew its appeal without explanation.

Even with legal wins, research universities have remained jittery about possible cuts to federal funding for research overhead. Officials at George Washington University, Yale University and University of California, San Diego have cited the threat of lower indirect cost reimbursement when signaling looming budget cuts or layoffs.

Groups take on DEI-related grant purges at NIH, NSF

In February, NIH began a systematic purge of all grants that contained any whiff of diversity, equity and inclusion elements, along with other topics anathema to the Trump administration, such as climate change and gender identity. Hundreds of previously approved grant projects ground to a halt, according to researchers and organizations that sued NIH in April.

Plaintiffs alleged the agency’s leaders “upended NIH’s enviable track record of rigor and excellence, launching a reckless and illegal purge to stamp out NIH-funded research that addresses topics and populations that they disfavor.”

They argued that the grant terminations include topics that NIH is required by law to research, many involving life-threatening diseases. They further argued NIH’s purge violated the Administrative Procedures Act, exceeded constitutional limits on the executive branch’s authority and were unconstitutionally vague.

Sixteen state attorneys general also sued in April over the anti-DEI policy in a case that merged with that of the researchers. In late December, NIH settled with the 16 states over delays in grant approval. Without conceding to the claims of the attorneys general, the federal agency agreed to restart the review process without using the anti-DEI directive.

In June, U.S. District Judge William Young concluded the NIH’s anti-DEI directives were illegal and ordered NIH to reinstate the funding, which would have amounted to over $780 million. But in August, the Supreme Court dealt a blow to the plaintiffs — and others seeking relief from mass grant cuts under the Trump administration.

A 5-4 majority ruled that the district court lacked jurisdiction to restore the funding. Instead, grantees must pursue their case through the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which hears monetary claims against the federal government.

The high court left intact Young’s order deeming NIH’s actions illegal, but grantees will still have to pursue their claims for funding restoration separately.

At the time, Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell — who represents a state rife with research universities and institutions — called the Supreme Court’s ruling “wrong and deeply disappointing.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson also rebuked the court's conservative majority, writing that their decision “neuters judicial review of grant terminations by sending plaintiffs on a likely futile, multivenue quest for complete relief.”

The Trump administration appealed Young’s ruling in June, and the case remains in the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The National Science Foundation undertook a similar grant culling last April. On its website, NSF said it would terminate grants that were “not aligned with program goals or agency priorities,” including research related to DEI, environmental justice and misinformation.

Once again, the Trump administration drew legal challenges to cuts.

In September, a federal judge declined to restore $1 billion in mass grants cut by NSF, saying that she lacked the authority to do so after the Supreme Court’s decision in the NIH lawsuit. The case against the NSF’s anti-DEI policy is still being argued in district court.

Students and faculty challenge Rubio and deportations

“In the United States of America, no one should fear a midnight knock on the door for voicing the wrong opinion.”

So reads the first sentence in a lawsuit filed in August by The Stanford Daily, the independent student newspaper of Stanford University, against U.S. State Secretary Marco Rubio and U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem over attempted deportations of students deemed to have anti-American or anti-Israel views.

Represented by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, the newspaper alleged that student writers were turning down assignments related to the Israeli-Hamas war or asking to have their published articles taken down over concerns their reporting would endanger their immigration status.

The case remains open. In January, the judge denied the Trump administration’s motion to dismiss the case. The plaintiffs seek a summary judgment against the government.

An earlier lawsuit, brought in March by the AAUP and others, tackles a similar issue. That action followed the arrest by immigration agents of Mahmoud Khalil, a former Columbia graduate student and legal permanent resident who was active in pro-Palestinian protests in 2024 and the lead negotiator representing students to university officials during their protest encampment that spring. After Khalil’s arrest last March at a university housing complex, Trump said it was the first “of many to come.”

Plaintiffs argued that the administration’s policy of detaining and threatening to deport critics of Israeli or U.S. actions has “far-reaching implications for the expressive and associational rights,” including those of U.S. citizens attending American universities.

“The fact that our brothers and sisters who don't have status didn't feel like they could speak — that actually deprives us of a right to have a more engaged and diverse dialog,” AAUP's Wolfson told Higher Ed Dive in January.

In a September ruling in the AAUP case, District Judge William Young, a Reagan appointee, found the Trump administration’s actions unconstitutional.

“This case — perhaps the most important ever to fall within the jurisdiction of this district court — squarely presents the issue of whether non-citizens lawfully present here in United States actually have the same free speech rights as the rest of us,” Young wrote. “The Court answers this Constitutional question unequivocally ‘yes, they do.’”

In a final ruling in January, Young ordered that the original immigration status be reinstated for the plaintiffs’ affected members unless it had expired, the person was convicted of a crime after September 2025, or the government had an appropriate reason under immigration law to alter their status.

Texas’ after-dark campus speech restrictions are contested

In 2019, Texas enacted a law aimed at ensuring “free, robust, and uninhibited debate and deliberations by students” at public colleges. It directed institution leaders to maintain common outdoor areas as areas for expression, discipline students who interfered with the expressive activities of others, and to not override student groups’ speaker choices over controversy.

Just six years later, Texas state lawmakers last summer passed a law banning all First Amendment-protected speech and expression on public college campuses between the hours of 10 p.m. and 8 a.m.

The bill’s sponsor framed it as a response to pro-Palestinian demonstrations on campuses both within Texas and across the nation. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott decried such protests at University of Texas at Austin as antisemitic and called for protestors to be arrested and expelled.

The law also bars voice amplification and drums or other percussive instruments during the last two weeks of any term.

In early September, FIRE sued the University of Texas System on behalf of several student groups, asking a federal court to declare the bans unconstitutional and to bar university leaders from enforcing the law on campuses.

FIRE chided Texas for what it called a “stunning — and blatantly unconstitutional — about-face on its stance toward protecting free expression and upholding the First Amendment at its public universities and colleges.”

“Early morning prayer meetings on campus, for example, are now prohibited by law,” the complaint argued. “Students best beware of donning a political t-shirt during the wrong hours. And they must think twice before inviting a pre-graduation speaker, holding a campus open-mic night to unwind before finals, or even discussing the wrong topic — or discussing almost anything — in their dorms after dark.”

In October, U.S. District Judge David Alan Ezra, a Reagan appointee, issued a preliminary injunction barring enforcement of the new rules on University of Texas campuses. In the ruling, Ezra wrote that plaintiffs raised “significant First Amendment issues” with the law.

“The First Amendment does not have a bedtime of 10:00 p.m.,” the judge wrote. “The burden is on the government to prove that its actions are narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling governmental interest. It has not done so.”

Possibly one of the more restrictive speech laws in the country, Texas could be a test case for how far state governments can go in regulating expressive activity on college campuses.