Dive Brief:

- A federal judge declined to temporarily block the enforcement of a state law that bans public colleges from funding diversity, equity and inclusion programs and from compelling students to affirm certain “divisive concepts.”

- Earlier this year, a group of students and faculty members sued the state’s governor and the University of Alabama’s trustees over the new law, arguing that it violates their free speech rights by placing viewpoint-based restrictions on what can be taught in the classroom. They also contended that the law undermines due process by being so ambiguous that instructors and students don’t know what is prohibited.

- U.S. District Judge R. David Proctor — a George W. Bush appointee — pushed back on those arguments in his 146-page ruling Wednesday. Proctor denied their request for a preliminary injunction, writing that public colleges could reasonably control curricular content and rejecting assertions that the law’s language is impermissibly vague.

Dive Insight:

Last year, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed a law known as SB 129, which bans public colleges and K-12 schools from having DEI initiatives. It defined those efforts as programs, training or other events where attendance is based on “race, sex, gender identity, ethnicity, national origin, or sexual orientation.”

PEN America noted last year that while this language doesn’t outright ban all DEI initiatives, the attendance restrictions could bar public colleges from activities like creating programming specifically for international students or recognizing a Black student union.

The law also barred public colleges from requiring students to affirm or adhere to a list of so-called divisive concepts.

Under the law, one of the concepts is that individuals “are inherently responsible for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race, color, religion, sex, ethnicity, or national origin.” Another is that people are “inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously” based on their personal characteristics.

The law also contains carve-outs. It says that the language does not bar public colleges from teaching or discussing divisive concepts “in an objective manner and without endorsement as part of a larger course of academic instruction.”

According to court documents, faculty members who sued over the measure said that while they do not require students to affirm or adhere to these concepts, they worry that their instruction on race and gender could be viewed as running afoul of the law — even with the carve-outs for teaching.

“I do not know what it means to discuss a divisive concept ‘in an objective manner’ and ‘without endorsement,’” plaintiff Cassandra Simon, a social work professor at University of Alabama, said in court documents. “There is robust empirical evidence of implicit bias, white privilege, and the absence of a colorblind meritocracy. I am unable to determine whether continuing to present these scholarly findings, and assigning readings on these subjects, would violate SB 129.”

One of Simon’s class assignments — that students select a social issue of their choice and advocate for it — was abruptly canceled due to the law, according to court documents.

Her students chose to hold a sit-in to protest SB 129 for their project. The day of the sit-in, however, the social work dean told Simon to cancel the assignment in part over concerns that it would compel students to agree with one of the banned divisive concepts.

Another plaintiff raised concerns over teaching about topics such as structural racism, employment discrimination and health disparities by race. And another voiced concerns that the law potentially limits his ability to teach about eugenics.

However, Proctor wrote in his ruling that the law doesn’t prohibit the teaching of divisive concepts and pointed to the carve-outs provided.

The judge also cited an appeals court case that found a public college could “reasonably control the content of its curriculum, particularly that content imparted during class time.”

“There is no legal basis for concluding that the First Amendment protects a university professor’s academic freedom in the way the Professors suggest,” Proctor wrote.

Referring to the canceled sit-in, Proctor wrote that it was “a reasonable exercise of control over course curriculum to ensure that students would not feel coerced into advocating for a belief with which they disagreed.”

Proctor also dismissed Ivey as a defendant in the case, ruling that plaintiffs’ alleged injuries aren’t traceable to her.

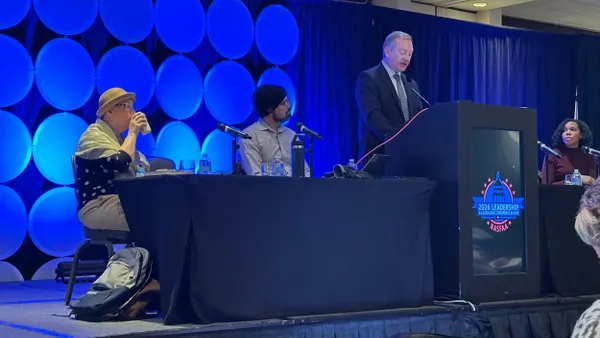

The plaintiffs in the case slammed the decision on Thursday.

“SB129 created a culture of fear that has severely hindered the ability of professors to provide comprehensive instruction in our areas of expertise,” Dana Patton, a University of Alabama professor and plaintiff in the case, said in a statement. “The law infringes on our academic freedom and our duty to students to provide a truthful and comprehensive education.”

Alabama state Sen. Will Barfoot, the sponsor of the legislation, didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.