While international student enrollment has remained relatively flat overall so far, student visa experts and university leaders say that might change as the Trump administration’s restrictive visa and immigration policies could deter new enrollment of this population.

Recent surveys and studies have shown declines in new international enrollees, indicating that the Trump policies could have affected their ability to enroll in U.S. colleges for the fall 2025 term.

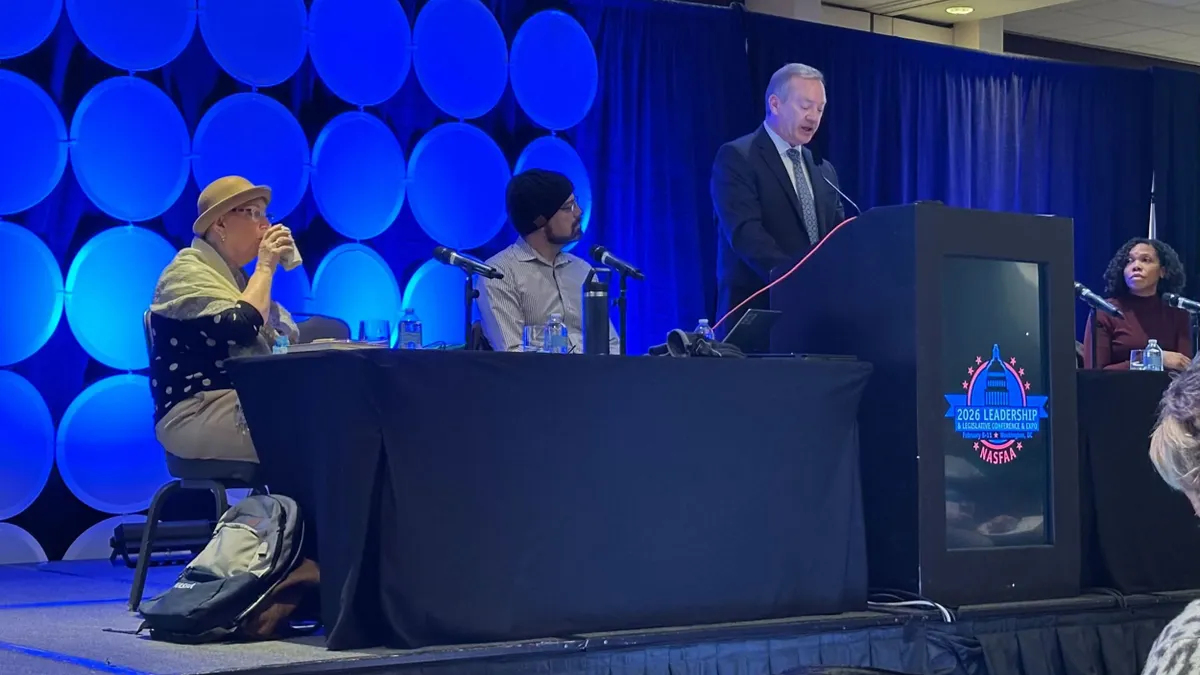

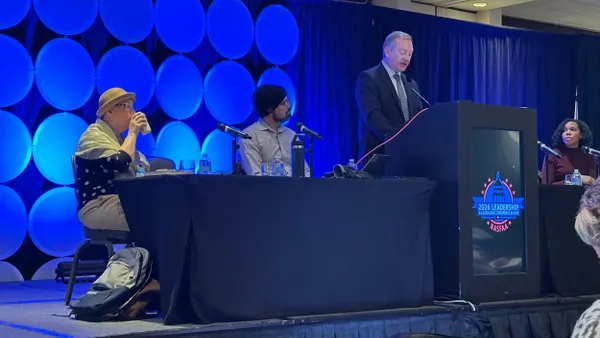

Shifts in U.S. visa and immigration policy have forced institutions to navigate “one of the most dynamic moments in international education,” Fanta Aw, executive director of NAFSA: Association of International Educators, said in an email.

“The ripple effects of these policy changes are being felt across campuses and communities around the world,” she said.

Finding ways to recruit and welcome international students — through efforts like diversifying outreach efforts to different countries and providing international students with flexibility on when they must start their studies or make payments — is crucial for many institutions, experts say.

Large universities and state colleges with high shares of international students could be hurt by international enrollment losses — but not to the extent as smaller, often faith-based, institutions that enroll a high percentage of these students, said Dick Startz, an economics professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Augustana College, a small Lutheran institution in Illinois, saw its new international enrollment decrease to 140 students in fall 2025, 30 fewer students than the year prior, according to W. Kent Barnds, executive vice president for strategy and innovation. Applications from international students fell by more than 10%, Barnds said in an email.

Barnds attributed the decrease to Trump administration policies, including last summer's temporary pause on student visa interviews, as well as to students opting to pursue college elsewhere due to “a perception that the US is increasingly hostile to international students studying here,” he said.

Some institutions have announced plans to cut spending due to losses in international students.

In one example, DePaul University — a Chicago-based Catholic institution — saw international enrollment fall by about 755 students year over year for fall 2025, including a nearly 62% decline among new international graduate students, the university told faculty and staff in a September letter.

"Because of the challenges to the visa system combined with the declining desire for international students to study in the U.S., we are seeing massive disruptions to our enrollments in many areas around the university," DePaul’s top leaders wrote.

International students typically want to go to English-speaking colleges and universities, particularly ones in the U.S., Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, said Startz.

But Startz said he’s heard anecdotally that school guidance counselors in China were reaching out to English-speaking colleges in Hong Kong and Singapore as an alternative out of fear their students might not be able to get into the U.S.

“Right now, we would have a real opportunity to grow our market share, but we seem to be putting in policies to go in the other direction,” said Startz.

Policies that could hurt enrollment

President Donald Trump has publicly supported making the U.S. more open to international students.

In a November interview on Fox News, Trump said that curbing such enrollment would put many colleges out of business. A few months earlier, he said he would allow 600,000 Chinese students to enroll at universities in the U.S. That’s more than double the nearly 266,000 Chinese students enrolled at American institutions during the 2024-25 academic year.

But despite those comments, his administration’s policies have moved in the opposite direction.

The Trump administration in May ordered consulate offices to stop scheduling visa interviews with international students as officials worked on a policy to more rigorously vet applicants' social media accounts. Officials eventually lifted the freeze in June, but the pause created a period when international students couldn't obtain a visa at all, followed by a backlog of applications awaiting approval, said Startz.

Due to the pause, some students likely did not get a visa in time for the fall term, some may have decided to wait until the spring term to attend, and others might have been discouraged from attending completely, Startz said.

Since the second Trump administration took over, the State Department has also revoked about 8,000 visas from international students, including some who participated in pro-Palestinian campus protests. This sent a discouraging message to students that they could lose their visas for protesting on campus, said Sarah Spreitzer, vice president of government relations at the American Council on Education.

The administration has also cut federal research grants— totaling a loss of $1.4 billion in National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation grants in 2025, Nature found. And Trump has issued an executive order giving political appointees oversight on grant approvals to ensure they adhere to this administration’s priorities.

The policies, Spreitzer said, have left some international students in U.S. graduate programs uncertain of whether they will continue receiving federal financial support — prompting them to consider leaving.

Meanwhile, places like China, France, and the European Union are actively trying to recruit researchers and graduate students who are currently in the U.S., Spreitzer said.

Moreover, the Trump administration proposed a rule in August that would cap at four years the time international students are allowed to complete their program, with an option to apply for extensions and undergo "regular assessments" by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. That’s in contrast to the existing policy that allows them to stay for as long as they’re pursuing their programs. The change has not yet been finalized.

Many students can finish their undergraduate degree within four years, but the proposed policy could prevent international students from completing a double major, enrolling in a study abroad program or completing a co-op program open to their domestic peers, said Spreitzer.

“People who are expecting to spend six or seven years coming here and taking classes, working in labs — if they're told they can only get a visa for four years, that really could discourage people,” Startz said.

New international enrollment drops

Overall, international student enrollment has remained flat recently, according to the most recent data, but it appears federal policies have had an impact on new student enrollees.

Among 828 U.S. colleges surveyed last fall, international enrollment declined just 1%. However, new international enrollment dropped a whopping 17% at those institutions, according to a report from the Institute of International Education and 10 partner higher education groups.

Another survey — from NAFSA, the Oxford Test of English, and Studyportals — found a 6% average decline in new undergraduate international students and a 19% drop among new international master’s students at some 200 U.S. institutions.

Both polls linked U.S. visa policies to the declines. A majority — 85% — of institutions surveyed for the NAFSA report indicated that restrictive visa policies were major obstacles to enrolling international students. That is up from 58% in 2024.

A recent National Student Clearinghouse Research Center report also revealed a year-over-year decline of 10,000 international students enrolled in U.S. graduate programs for fall 2025, though undergraduate international enrollment ticked up.

How colleges are responding

According to the NAFSA report, 28% of institutions are anticipating budget cuts over the next year to adjust to the ongoing uncertainty over international enrollment.

However, declines in international students won't be felt evenly across the higher education sector, as some institutions will likely see larger declines and budget impacts than others, said Spreitzer.

This challenge, of course, isn't the only one colleges are facing. They are also grappling with losses in federal grants, uncertainty in overall federal funding and changes to student loan programs. Some are also experiencing enrollment declines due to a smaller pool of college-aged students, said Spreitzer.

“International enrollment is one piece of the financial puzzle for our institutions,” said Spreitzer.

Universities are adapting to international enrollment challenges by recruiting students in new markets, expanding online pathways, and growing their collaborations and partnerships with other universities, said Cara Skikne, head of communications and thought leadership at Studyportals, a foreign student recruitment firm that collaborated on the NAFSA report.

After losing new international students in the fall, Augustana College, for example, refocused its recruiting efforts on countries where more visa interview appointments were available, said Barnds.

International enrollment from China has declined recently, spurring some institutions to recruit more students from other areas such as India or various African countries, said Spreitzer. China is the second largest source of international students in the U.S., behind only India, according to IIE.

“Right now, we would have a real opportunity to grow our market share, but we seem to be putting in policies to go in the other direction."

Dick Startz

Economics professor, University of California, Santa Barbara

Roughly half of all U.S. institutions prioritized undergraduate recruitment outreach in Vietnam and India, and nearly 40% prioritized students from Brazil and South Korea, IIE’s fall snapshot found. At the graduate level, most colleges and universities, 57%, focused their recruitment efforts on India, while 32% focused on Vietnam, and 28% targeted both China and Bangladesh, the snapshot added.

Over a third — 36% — of U.S. colleges plan to diversify their international markets over the next year, the NAFSA report stated. Another 26% expect to expand their online programs as an alternative enrollment pathway for international students.

“Over-reliance on one or two major source markets makes universities vulnerable to sudden policy changes or economic shocks,” Skikne said in an email.

Some institutions might also boost their international recruitment outreach, said Startz. But that work is expensive so the extent to which they can do so is limited, he said.

Institutions can help students navigate last-minute visa processing hurdles at a low cost by offering hybrid start options — meaning they would start online and come to campus later — and extending payment deadlines, Skikne said.

Last fall, 72% of institutions offered international students deferrals to spring 2026, while 56% offered deferrals to fall 2026, according to IIE’s fall 2025 snapshot.

Despite institutional efforts to make international students feel welcome, those students have also read about the Trump administration’s policies and political rhetoric, said Skikne. Plus, they're sharing stories in group chats about having their visas rejected or feeling unwelcome in the U.S., she said.

Enrolling in the U.S. is an enormous financial decision for an international student, Spreitzer added.

“If there is uncertainty around whether or not your visa is going to be valid the entire time, or whether or not you’ll be able to finish your degree before being asked to leave the country,” said Spritzer, “I think that you might start looking around to other places.”