It's been a month since policymakers patched together a quick fix to prevent the University of California, Berkeley from having to cut 2,629 on-campus students from its fall enrollment.

Yet the case sticks in the mind. Why? Because of what it suggests for higher ed leaders at institutions across the country who have to grapple with a seemingly ever-expanding list of constituencies — constituencies that champion their interests loudly, work the courts or control public purse strings.

There's a reason the term town-gown relations is well known. But UC Berkeley's situation stands out because of how years of disagreements and decisions boiled down to one brief period where it seemed just about everyone was poised to lose.

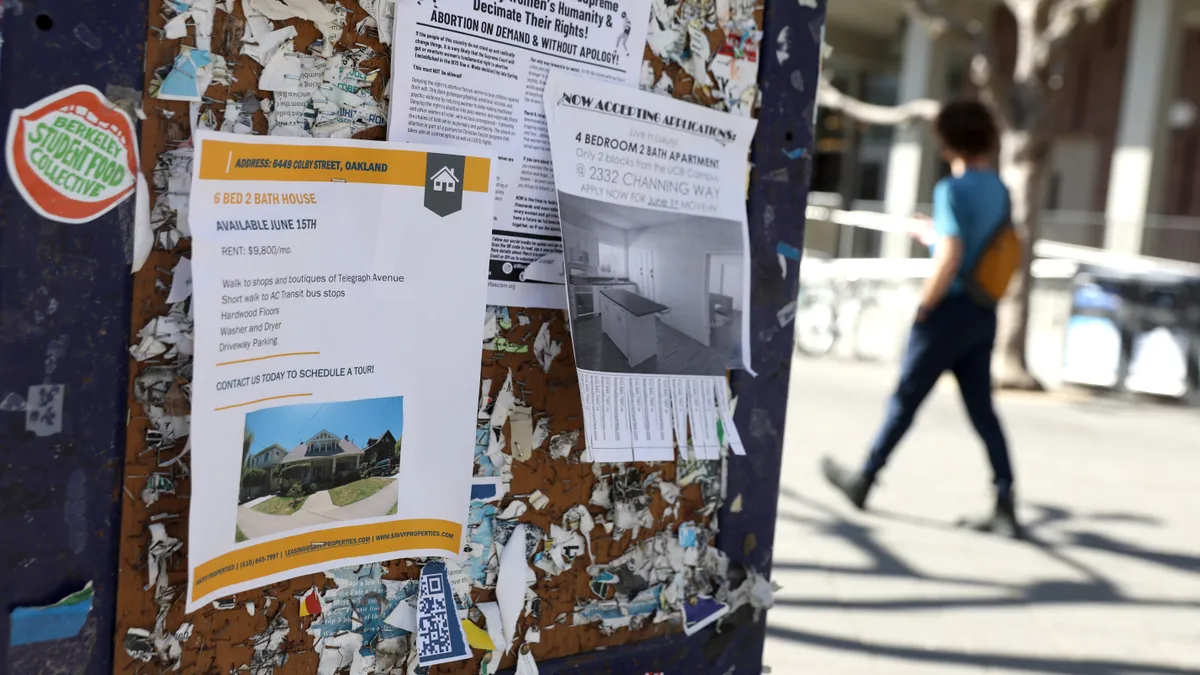

To quickly recap the most important facts: The California Supreme Court in early March held up a lower court's order freezing UC Berkeley's enrollment until the university conducted a study of how growing its student population would affect local conditions. The decision, which stemmed from a city residents' group suing under a state environmental protection law, meant the university needed to revert its on-campus enrollment to 2020-21 levels.

UC Berkeley responded by publicly releasing plans to conform to the court order, including shifting students to remote and off-campus learning and not enrolling 400 mostly graduate students. State lawmakers scrambled, amending the law cited in the judge's ruling and allowing Gov. Gavin Newsom to sign legislation avoiding the crisis 11 days after it came to a head.

One popular way to dissect the situation was through the lens of NIMBYism — the not-in-my-backyard arguments local residents use to fight new development. The group bringing the lawsuit, Save Berkeley's Neighborhoods, says it is campaigning over UC Berkeley's "failure to study the environmental impacts of the huge increase in student enrollment and its failure to mitigate the impacts on our community."

UC Berkeley doesn't determine its own enrollment levels, a university spokesperson told me shortly after the state Supreme Court issued its ruling. As a public institution that's part of a larger system, it has to account for direction from California's governor, state lawmakers, the UC system's board of governors and the system's Office of the President, said the spokesperson, Dan Mogulof.

Indeed, the University of California system in the fall touted plans to add 20,000 students by 2030. Where those students go could be a source of future conflict, particularly because the most selective universities — like UC Berkeley — are expected to be in the most demand.

The university knows it has a capacity problem. Its leaders have talked about a "student housing crisis" and laid plans to double the number of beds in housing it owns or operates. Mogulof said Save Berkeley's Neighborhoods has been standing in the way of the university's efforts.

"These same litigants have sued us to try and stop each and every housing project that's part of this initiative that we've tried to launch so far," Mogulof said.

The president of Save Berkeley's Neighborhoods, Phil Bokovoy, sees it differently.

"We've been willing to sit down for years at this point to get an agreement that ties enrollment growth to housing production," Bokovoy said. "They have promised to build housing in the past and didn't, and they went ahead and increased enrollment. We don't trust them to build the housing that they say they're going to build."

The situation is like something out of a political science textbook. Lisa García Bedolla, a professor at UC Berkeley's graduate school of education, pointed to tensions among different levels of government.

"When you have overlapping jurisdictions, this is what happens," García Bedolla said. "The complexity of our system can create this sort of public train wreck."

Also important is the tension between whether higher ed is a public good or a private good.

Viewed as a public good, institutions like Berkeley should benefit society at large by pushing research boundaries and producing graduates whose contributions to society help drive up everyone's quality of life. But education can also be seen as a private good benefiting students at the expense of others who pay for their college attendance — either directly through tax dollars that subsidize tuition or indirectly by living next to a growing university.

And not everyone has access to higher ed as a private good. UC Berkeley rejected about nine in every 10 undergraduate applicants in 2021, meaning most people who apply are shut out.

Lawmakers can be attuned to that question of access. But are they as sensitive to the question of funding the infrastructure needed to support sending more students to competitive colleges? And are elite college leaders willing to see their admit rates rise, in turn lowering the selectivity metrics their peers watch closely?

None of this is meant to be a commentary on how UC Berkeley's leaders handled this particular situation. There are simply too many nuances involved to explore here. The point is that mapping out the different constituencies in this case might help college leaders involved in other complex conflicts.

Don't make the mistake of thinking these considerations only apply to public colleges or selective ones. Residents across the country fight for private nonprofit institutions that are exempt from property taxes to make payments to municipalities. Lawmakers are questioning private colleges' tax-free status. Decisions about capacity and funding for selective institutions inevitably affect other colleges across the higher ed sector by reshuffling their incentives and niches, particularly as student demographics are expected to change.

UC Berkeley's case can be a prompt to think about these issues because it was so dramatic. A court ruling was poised to shift the cost of past growth from one set of residents onto a single class of students — the one expecting to enroll in the upcoming fall.

Ultimately, lawmakers shifted back toward the status quo. Save Berkeley's Neighborhoods wasn't happy, with Bokovoy saying in a statement that the change in the law "gives the UC a unique free pass."

If the underlying issues aren't resolved, when will the next court order bring into sharp relief the tensions between town and gown?

"We have a problem where we need places to put kids so that they can go to school, which is in all of our interests," García Bedolla said. "But then who has the immediate cost of that growth?"