When Michigan launched a free college program for frontline workers last year during the pandemic, state officials expected to receive around 15,000 applicants. Instead, the program, called Futures for Frontliners, drew 120,000.

"It was kind of a proof point, if you will, that demand is high in our state for this opportunity," said Kerry Ebersole, director of Michigan's Sixty by 30 initiative, which aims for 60% of the state's working adults to have a postsecondary credential by 2030.

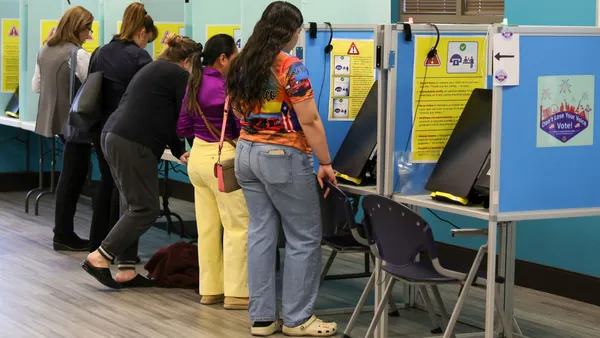

Just a few months later, the state created another free college program. Called Michigan Reconnect, it targets residents who are 25 or older with a high school diploma but no further degrees. Within six weeks, the program received more than 60,000 applications.

Both initiatives are part of Michigan's Sixty by 30 goal, which relies on increasing college-going rates from recent high school graduates as well as enticing adults to gain postsecondary credentials. Around 45 states have similar attainment goals, yet free college programs that are open to adult students, typically considered to be those ages 25 and older, are uncommon in higher education.

Fourteen out of 23 statewide free college programs exclude adult and returning students, while many of those that don't leave them out have stringent participation requirements that "effectively do the same," according to a report last year from The Education Trust. Just two programs in its sample were designed for older students.

The landscape may be shifting, however. The pandemic reinvigorated calls to upskill large swaths of the population, and its harm to the economy also highlighted the need for states and colleges to remove potential cost barriers to postsecondary education.

"Finances will no longer be the barrier to getting a college degree if you're over 25," said Mike Hansen, president of the Michigan Community College Association. "As we start to see increasing requirements of higher skills … you'll also see therefore the demand pick up for adult students to come back."

Looking to Tennessee for help

Michigan lawmakers set aside $30 million to fund the Reconnect program, which pays for students' remaining tuition after all other state and financial aid has been applied. The measure garnered bipartisan support by being billed as a workforce development initiative, even though free college proposals nationwide are more contentious.

"Name an industry anywhere in the country, and there's going to be a shortage of skilled people to fill jobs there," said Michigan state Sen. Ken Horn, a Republican who helped spearhead the legislation. "It doesn't matter — Republican, Democrat, what region of the state you're from — we have people on board with this issue because it truly solves the problem."

Michigan isn't the first state to launch a free college program for adult students. It drew inspiration from Tennessee, a red state that pioneered free college programs for students coming straight from high school as well as for older learners

Tennessee created its program for the former group in 2014, but lawmakers and industry leaders complained that adults were left out, said Emily House, executive director of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. Four years later, it launched Tennessee Reconnect for those classified as independent students.

In its first year, nearly 42,000 people applied for the Tennessee Reconnect grant, and more than 18,000 enrolled in an associate degree or certificate program and received aid, which covers tuition and fees after all other state and federal assistance has been applied.

Program participants "overwhelmingly identified" finances as their biggest hurdle to pursuing a college credential, according to a state analysis of the program. They also ranked family responsibilities, work demands and time management as concerns.

More than 2,000 students completed a degree or certificate during the first year, and 248 of that group stayed enrolled to pursue another credential. "That first year was just beyond anything we could have imagined," House said. "It's very much just become part of the suite of financial aid initiatives that we offer in Tennessee, and it's part of the conversation in a way it wouldn't have been five years ago."

Michigan Reconnect features some of the hallmarks of Tennessee's program.

In Michigan, "success coaches" at the community colleges will serve as a point person for adults pursuing a credential under the program, Ebersole said. It's also hiring another set of advisers, which the state calls "navigators," that can help students through the application process.

Tennessee Reconnect has people called navigators serving a similar function. "Financial aid is really like the make or break for some of these adults," House said, "but I think to some extent the mentorship and the support is definitely equally important."

Supportive policies at the college level

Community colleges must also be ready to serve more adult students, who often have competing work and family obligations that necessitate more flexibility at school. The pandemic hurt enrollment at public two-year institutions, including many in Michigan, with the sector's headcount declining 10% year over year nationwide last fall.

Michigan's community colleges expect the state's two free college initiatives to jumpstart enrollment. Officials at Wayne County Community College, in Detroit, added a shortened term to let students take advantage of Michigan Reconnect as soon as possible rather than wait weeks or months for the regular summer term to begin.

"Mostly, all the colleges had no choice but to say, ‘Okay, great, you're here, (but) you have to wait for our summer semesters," said Brian Singleton, the college's vice chancellor for student services. "I think that's wrong for students."

All of the roughly 30 classes comprising the subterm were filled. "When they have that fire and they want to continue, you have to accommodate that — you have to get them in right then and there," Singleton said.

"Financial aid is really like the make or break for some of these adults ... but I think to some extent the mentorship and the support is definitely equally important."

Emily House

Executive director, Tennessee Higher Education Commission

Colleges can make other changes to help adult students complete credentials in a timely manner. "We know time is money, and especially for adult students," said Christine Carpenter, senior vice president of engagement at the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning.

Schools should recognize a student's accumulated knowledge, Carpenter said, including by accepting transfer credit and through prior learning assessments.

The American Council on Education is likewise calling on colleges to improve their credit transfer policies so students don't stop making progress toward a credential. Credit loss "is occurring to a much larger extent than it should," the group contends in a recent report.

PLA, which awards students college credit for learning they've gained through work experience, is another underused method for helping adult students complete a credential, suggests recent research from CAEL and the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. It found that nontraditional students who earned credit through PLA are more likely to complete a credential than those who don't.

Financial relief through other means

Free tuition isn't the only tool states and colleges can use to remove financial barriers for adult students. In Michigan, a patchwork of schools is hoping to bring back students who left without completing a credential by forgiving some of their debt.

Wayne State University, a public regional institution in Detroit where one in five students is age 25 or older, has been spearheading the effort. In 2018, it launched the Warrior Way Back program, which forgives students one-third of their balance to the institution of up to $1,500 total for each semester they successfully complete, for up to three semesters.

Students are eligible for the program if they haven't attended Wayne State for at least two years and have a grade point average of 2.0 or higher.

Because federal financial aid cannot be used for past-due balances, the program removed a major obstacle for students who accumulated debt, said Dawn Medley, Wayne State's associate vice president for enrollment management. "It wasn't that they were out of financial aid or didn't have means to pay, it's just they couldn't come up with a chunk out of pocket to clear that past balance," Medley said.

"We know time is money, and especially for adult students."

Christine Carpenter

Senior vice president of engagement, CAEL

The program has been relatively small so far. About 250 students have participated, of whom more than 50 have graduated.

Yet it has had a positive return on investment for the university. So far, Wayne State has received more than $1.6 million in tuition revenue from students who returned due to its debt forgiveness policy. And the effort has spread to other colleges, including nearby Henry Ford and Macomb community colleges.

The goal was "to create a sort of ripple effect across the region to incentivize other institutions to similarly examine what they could do to serve this low-income, adult student population better," said Melanie D'Evelyn, director of education and talent initiatives for the Detroit Regional Chamber, a business advocacy group that is looking to improve the region's talent pipeline.

D'Evelyn and others hope such initiatives expand.

"When a state (or) a college can make a commitment to forgive debt or make college affordable, it really ensures adults have the opportunity to earn a credential," CAEL's Carpenter said. "It really provides opportunities that haven't been there before."