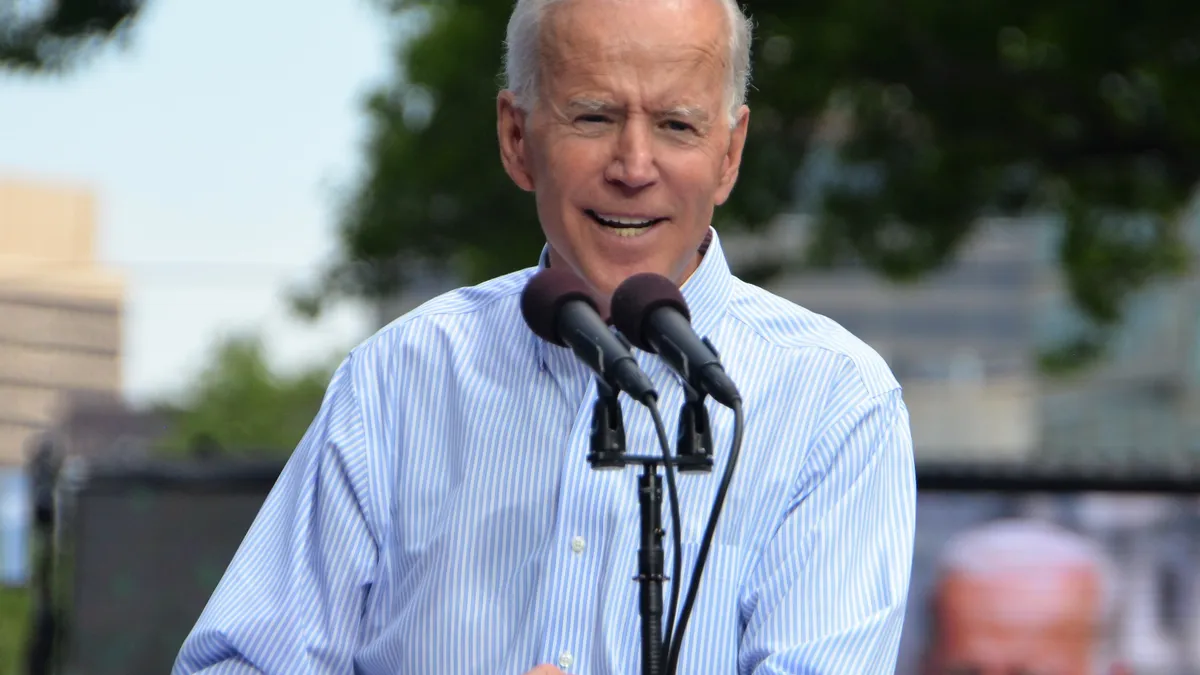

Joe Biden has said that, as president, he would dismantle Education Secretary Betsy DeVos' new regulation governing campus sexual assault.

But doing so would be a lengthy process, and one that would likely spur confusion among colleges. In part that's because a Biden Education Department could take several paths in administering Title IX, the federal law banning sex discrimination on college campuses. Among them are issuing a new regulation or guidance, or even pushing for new legislation.

Even if his administration pulled the department's rule entirely, institutions would still need guidelines for investigating and potentially punishing sexual violence. And until new rules or guidance is in effect, they would have trouble figuring out what to follow.

The statute has become heavily politicized in the last decade. Developing a policy that would endure long term and through a Republican-controlled executive branch would prove difficult, legal and policy experts say.

Evolution of Title IX

Biden helped elevate sexual assault prevention to the national forefront as vice president in the Obama administration, creating a federal task force and White House advisory position to bring awareness to the topic. As a Democratic senator representing Delaware in the 1990s, Biden also helped construct the Violence Against Women Act, a cornerstone federal law.

"This is a signature issue for him," said Brett Sokolow, president of the Association of Title IX Administrators. "It will be a high priority."

The Biden campaign did not respond to Education Dive's emailed request for comment.

But the Obama administration's best-known initiative to combat campus sex crimes was the Title IX guidance it proffered in 2011, which survivors and their supporters widely credit with providing them new protections.

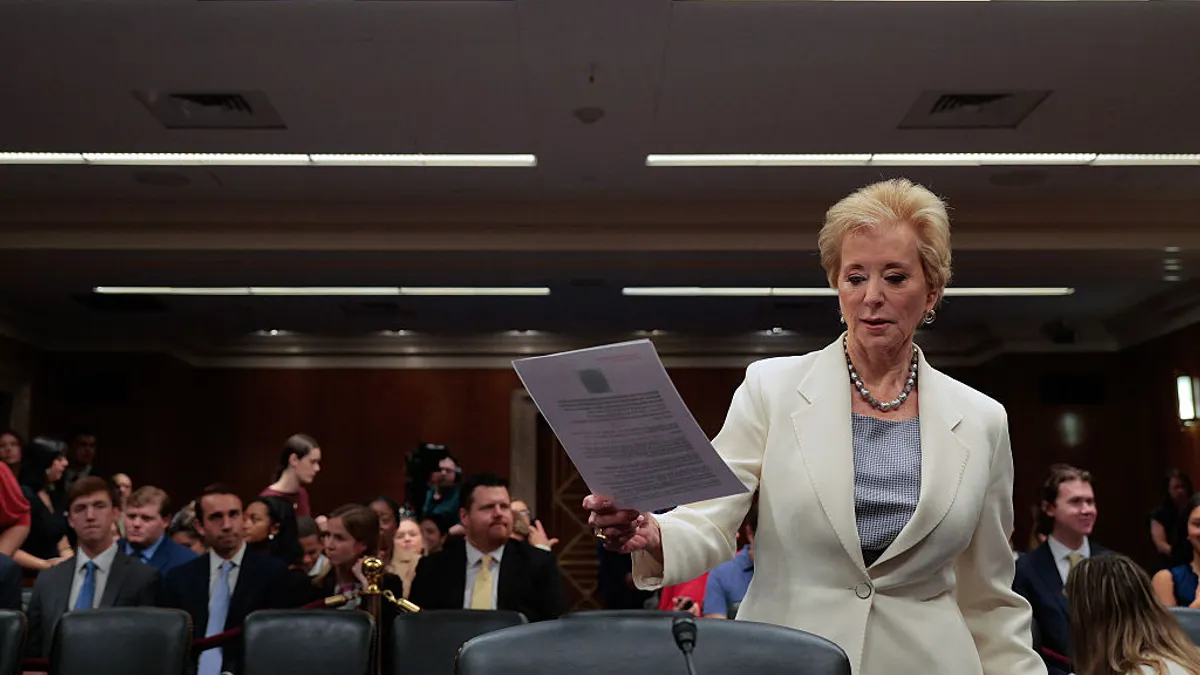

DeVos revoked this guidance early in her tenure, heeding the allegations of due process activists that institutions were under pressure to find accused students responsible for sexual violence, even with little evidence.

Many Title IX practitioners say it was not the Obama guidance that was flawed, but rather some institutions' interpretation of it. Nevertheless, lawsuits alleging college administrators flubbed or were discriminatory during investigations have skyrocketed in the last eight years.

DeVos' rule, which took effect in mid-August, means to correct the perceived injustices against the accused and creates a complex pseudo-judiciary system for considering sexual assault claims, which involves holding a live hearing. It also limits the cases colleges would need to investigate, eliminating many of those happening off campus or on study abroad trips.

Her mandate raised issues beyond colleges having only a few months to comply with the new rule — a 2,033-page document — amid a public health crisis.

Of particular concern is a provision forcing investigators to exclude evidence and statements that aren't brought up during a hearing, said Jody Shipper, a former Title IX administrator who co-manages consulting firm Grand River Solutions. Officials would be required to ignore an alibi for an accused student if it wasn't presented to the panel, Shipper said.

"If I were investigating that case, I knowingly would have to make a wrong conclusion, but I had to use the evidence I had," she said.

The new Title IX rules also clash with Title VII, which bans employment discrimination. Colleges have certain processes by which they discipline employees, but those likely no longer match the department's regulation. Some colleges have needed to revise their collective bargaining to align them, Shipper said.

Biden's experience with Title IX and similar policy matters suggests the administration likely would take a nuanced approach to fixing these problems, she said.

"Worst-case scenario is that (DeVos' rule) is withdrawn, and other pressing issues take over, and there's a two-year void where colleges don't know what to do," Shipper said.

What would Biden change?

Biden would almost certainly re-expand Title IX's jurisdiction, making it so colleges are responsible for all off-campus incidents, said Jake Sapp, deputy Title IX coordinator and compliance officer at Austin College.

He'd also likely undo parts of the mandated hearing process, Sokolow said, such as the new requirement that the two parties cross-examine each other through a surrogate, which survivor groups argue is retraumatizing.

Laura Dunn, an attorney advocating for survivors of sexual violence, said she fears accused students would hire lawyers as their hearing representatives, forcing victims to do the same. And few lawyers specialize in survivor rights, she said.

She would like to see Biden streamline Title IX processes and give institutions more flexibility. The new rule doesn't recognize the vast differences among institutions, Dunn said, noting that a beauty school with a handful of students doesn't need the same Title IX process as a large public university.

"This is an area with significant case law, and instead of trying to make a new landscape based on largely one perspective, we should develop one that keeps enough procedural protections with the goal of eradicating sexual assault."

Laura Dunn

Survivor advocate attorney

Colleges have largely escaped punishment by signing agreements with the department to make changes to their sexual misconduct policies, Dunn noted. These are "sweetheart deals," she said, pointing out that when Tufts University decided to revoke its Title IX agreement with the department in 2014, there were no consequences. Tufts eventually signed an agreement, after federal officials warned they might terminate its federal funding.

"I hope when Biden's people are building this they realize they don't have to guess," Dunn said. "This is an area with significant case law, and instead of trying to make a new landscape based on largely one perspective, we should develop one that keeps enough procedural protections with the goal of eradicating sexual assault."

Avenues for reworking Title IX

The DeVos rule went through the usual regulatory review process, garnering more than 124,000 comments, which were overwhelmingly critical.

A Biden administration could do the same, but the typical timeline means comprehensive changes might not come until the end of his prospective first term, as was the case with DeVos' regulation, Sokolow said.

Biden could also direct his education secretary not to carry out the regulation. However, doing so would open the administration to lawsuits by men's rights groups, Sokolow said, in the same way activists sued President Donald Trump's Health and Human Services Department for failing to enforce LGBT nondiscrimination protections.

A faster route would be to issue new guidance. But the Obama administration got flack for skipping the regulatory process when it did so, and the outcome would neither carry the force of law nor override court precedents that dictate procedures based on where a college is located. For instance, institutions in the Sixth Circuit, which covers Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee, must allow cross-examination, similar to DeVos' rule.

New and proposed legislation also may affect Title IX standards.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-NY, has proposed the Campus Accountability and Safety Act, which would fine schools up to 1% of their operating budget if they didn't meet the bill's requirements. Those include reworking campus disciplinary proceedings and entering into memoranda of understanding with local law enforcement.

And California's governor signed a law in September that directs colleges there that get state funding to develop certain Title IX procedures by 2022. These conflict with aspects of DeVos' rule. Sokolow said the state is likely banking on it being overturned.

Congress could also rewrite Title IX, which would be a more permanent solution. But Democrats would need to win a majority in both chambers for that to happen during Biden's term. And even then it would still be a heavy political lift, said Sapp, who tracks legal matters concerning that law.

"It would be amazing. A big move for sure," Sapp said.